On the photographic archive of Candida Höfer

In considering the physical and emotional response which Höfer’s work incites it appears that the question to be posed is not so much “What has Candida Höfer photographed in terms of interiors of famous and lesser-known archives, theatres and reading rooms?” as “Why has she photographed them?”.

In spite of, or due to, the lack of human presence in her photographs of interiors, Höfer appears to be framing a very human condition.

Knowledge is power. Power to control society. The collection and preservation of knowledge in the archive is the historical preservation of the ideological status-quo. Are Höfer’s images of the interiors of libraries, institutions, and civic buildings a visual archive of that power (Fig.1)?

Fig. 1 Candida Höfer, 2017. Rossiskaya Gosudarstvennaya Biblioteka Moskwa II. [180 x 212,5cm, Chromogenic print, Edition of 6]

Applying this lens to Candida Höfer’s oeuvre of images of the bastions of culture could reveal insights into her visual texts.

Artistic performance, spatially represented by the theatre, is the counterpoint to that status-quo, challenging it and extending its boundaries even from within the ideology’s own architectural representation (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Candida Höfer, 2017. Bolshoi Teatr Moskwa II. [70.9 x 102.8 in., 180 x 261,3 cm, Chromogenic print, Edition of 6]

Höfer’s early work looked at the visual cultural changes which migrant workers from Turkey were bringing to Germany, from which exploration she arrived at the impact of the built environment on people. Public and semi-public spaces became her photographic subjects, be it waiting rooms at railway stations or opera houses, iconic architecture or the city milieu. Through this work “she also realized that paradoxically the impacts of architecture are most intensely present when people are not in the image” (Galerie Zander n.d.).

Höfer’s detached photographs investigate not only forms and structures of spaces, but minute details, creating personal portraits of these spaces (idem). These personal portraits would appear to respond to and challenge the question why such an “anti-personal aesthetic has become so dominant in international art photography at the turn of the twenty first century” (Soutter 2018: 37).

In fact, these images take time to discover, and “when seen live, rather than in reproduction, the sharpness and detail almost boggle the mind” (idem: 45). I can vouch for this.

The question arises whether or not Höfer’s objectivity is a mask?

The viewer is given a sense of having maximum control over the space, with no sense of distortion. A cool light permeates the images producing an identifiable clinical style and as a body of work they “form an archive of power and privilege” (idem: 45).

Critical analysis of her body of work is offered little insight from the photographer herself.

“There is no explicit, voluntary choice on the spot or in the lab according to the historical context of the space, … I assume it is the space as space that drives such decisions.” Candida Höfer (Kennicott 2011).

Probed on the motifs in her images of interior spaces and her “psychology of social architecture” by art writer Elena Cué, the photographer responds “I am primarily interested in visual relationships within each singular space and the layers of use visible in that space. If over time my aggregated work contributes to broader insights, then that happens so to speak behind my back”. And when asked about the absence of people making them appear even more present, she reveals that this came out of a necessity “to avoid bothering people while I am working” which ultimately became a lesson about presence through absence (Cué 2016).

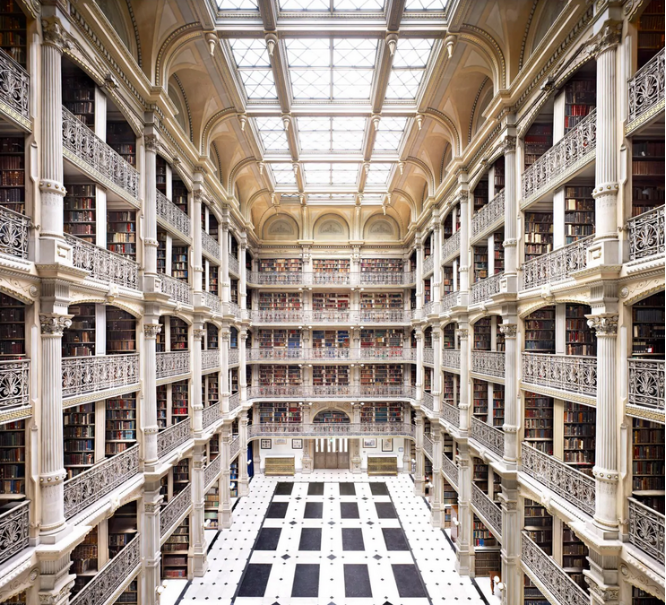

As with Bernd and Hilla Becher, the interpretation of the work seems to be handed to the reader of the visual text, which is left vulnerable to appropriation. This vulnerability is also a mask, as Höfer’s disembodied approach does not readily permit personal projection into the space (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Candida Höfer, 2010. George Peabody Library Baltimore. [71 1/2 × 77 3/8 × 1 3/4 in, 181.6 × 196.5 × 4.4 cm, Chromogenic print] (National Gallery ofArt, Washington, D.C., Collection of Robert E. Meyerhoff and Rheda Becker)

In her discourse on ‘Objectivity and seriousness’, whilst discussing Höfer’s work and the question of criticality, Lucy Soutter raises many questions, not least of which “is whether to represent something as objectively as possible is any more likely to produce a critical image than a celebratory one?” and in responding to her own question, reflects that many western readings consider Höfer’s images as “critical allegories about culture” (idem: 47).

Other interpretations consider them more celebratory. In his Washington Post review of a 2011 exhibition of Höfer’s work at the Baltimore Museum of Art, Philip Kennicott considers that “Höfer’s large-format photographs, with their deeply saturated color and extraordinary detail, have become a curious way to brand buildings, give them status, make them “celebrities.” There is something boosterish in using Höfer, whose work resists magazine-style loveliness, for cultural cachet, as if she can do for buildings what Andy Warhol did for celebrities.” (Kennicott 2011).

It could be countered that Warhol, after Abbott, was looking for the new heroes (Sutherland 2019) and anyway, who knows if Höfer is looking for heroes, or villains, or is just simply looking?

Kennicott comments on the disquieting uncanniness of the images which are “as haunting as they are stunning but also very chilly” and asks if through this ambiguity the photographer is “trying to idealize cultural institutions or reveal them as dead space or archaeological remains”? In conclusion, he considers that the images “want to say more, even if their urge to speak leads to ambiguous statements” and that there is a “sharper edge to these images, a hostility almost, that is bracing” (Kennicott 2011).

Patience Graybill in her study of Höfer’s library images (a subset of her ‘portraits of archival spaces’) posits that the photographer uses both “photography’s documentary attributes in historical archives or scientific studies” and “the medium’s more subjective aspects to make fictional, narrative images illustrate abstract or social concepts through their concrete subjects.” (Graybill 2007: 40). She considers that the recurrent subject of archival spaces inherently aligns Höfer’s work to cultural memory, or the collective negotiation around preservation of cultural inheritance, within the “arsenals of memory” of Western civilization (idem: 43).

Nevertheless, seen individually without knowledge of Höfer’s own photographic archive, Graybill suggests that the images “have only limited ability to postulate on the social significance of modern archival spaces”, partly because Höfer’s emphasis on specificity does not allow an individual image to generically represent all archives. Paradoxically, it is this specificity, or attention to detail, which leaves “viewers to puzzle out Höfer’s ambiguous pictures for their symbolic gestures and subtle implications”. It is, however, within the context of her body of work, that single images reach their potential “to reflect on the practical and symbolic functions of archival spaces in modern societies”. (idem: 45).

In consideration of Höfer’s body of work for the archives of women artists research and exhibitions, Pauline Gueland remarks on the photographer’s style being hallmarked “by a head-on treatment of an uninhabited architectural space” with the vanishing point dead centre of the image and often enhanced by a mirror effect from ceiling to floor. The question arises from any critical overview whether or not an entire oeuvre can be stamped with a singular hallmark, given that a body of work develops over decades, and cultures, artists and technologies change over time. Nevertheless, Gueland clearly identifies that in this “rigorous archival work, each photograph can only really be understood by its belonging to a much larger corpus.” (Gueland 2013).

As Lucy Soutter points out, critics often argue that Höfer’s “spaces do not invite us to project our own bodies into them but rather to contemplate them in the abstract (Soutter 2018: 46). Indeed, not all of the oeuvre takes this stance, as Patience Graybill remarks on the photograph Anna Amalia Bibliothek Weimar II, 2004 wherein Höfer “adopts a reverent sort of low-camera position” (Fig. 4). Here the viewer can enter into the image and feel the “the weight of cultural history” whilst gaining insight into a social inheritance propagated from the eighteenth century (Graybill 2007: 48).

Fig. 4 Candida Höfer, 2004. Herzogin Anna Amalia Library, Weimar II [87 2/5 × 70 9/10 in, 222 × 180 cm, Chromogenic print, Edition of 6]

As many critics point out, it is only once considered within this body of work, or in dialogue with other images -such as in the Galeria Helga de Alvear exhibition About Structures and Colors which has just eight photographs – that the individual images become intrinsically and forevermore imbued with their hidden social commentary.

In this way Hofer’s diligently constructed personal archive, put together over decades, reveals itself as a mask for an absentee visual text. I can’t help but wonder if this is not, ultimately, one of the underlying principles of all objective photography? Is it that the objective photograph is a mask for a serious study of a cultural theme, which can only be revealed by considering together images from within the body of work?

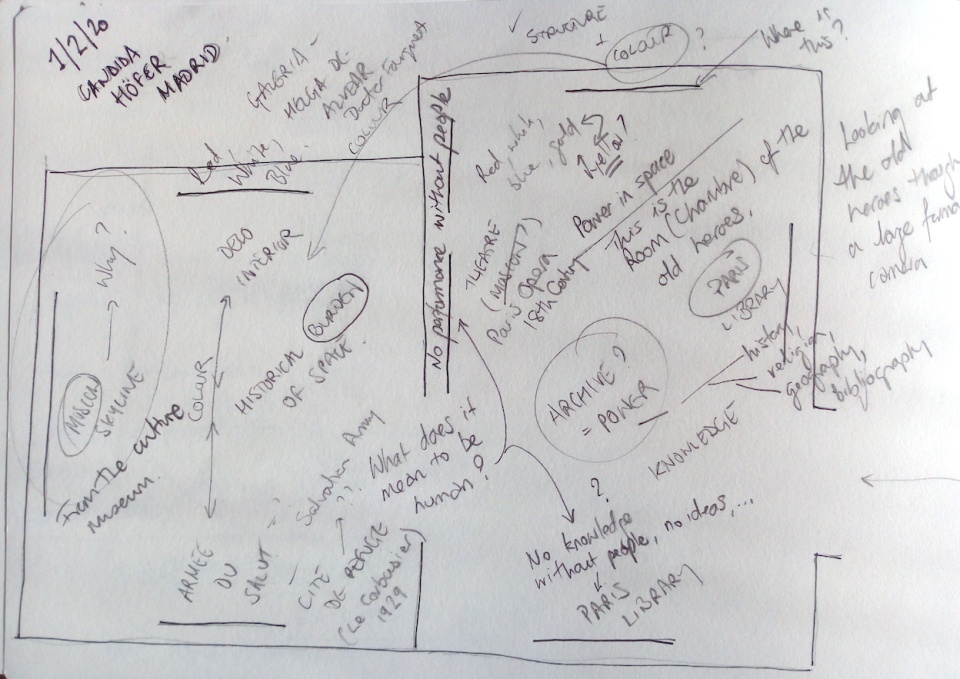

On About Structures and Colors

I visited the exhibition early on Saturday 1 February 2020. Most Madrilenians would have been recovering from their Friday evening out or getting ready for shopping in the busy city centre. This left the Galeria Helga de Alvear perfectly empty for me to immerse myself in, what can only be described as, the sumptuous scale and detail of Höfer’s large format prints.

Fig. 5 Interior of the Galeria Helga de Alvear (01.02.20) – First room looking through to second room

In About Structures and Colors, between images from Moscow and Paris, Höfer “reflects on the representation of national culture and architectural will through elements such as light, structure and color as well as the idea of beauty itself” (Galeria Helga de Alvear 2019).

The white walls are punctuated by four basic ‘colors’ – red, white, blue and gold/yellow. A nod to national identity and power structures represented in the images of civic spaces of 19th and 20th Century Moscow and Paris.

In the first room (Fig.5), immediate thoughts turn to humanity, to knowledge, performance and creativity. There’s no knowledge without people, no ideas, no reading in these empty libraries and no performance without stage players and audience (Fig. 6).

What does it mean to be human if you are absent? If all other humans are absent?

Fig. 6 About Structures and Colors, Exhibition Layout, Entry in my Final Major Project Workbook (01.02.20)

A darker question doesn’t immediately arise, but could it be that this is the room of the old heroes? Or indeed, were they ‘villains’, these heroes of the bourgeois?

A second room only hints at more social concerns, where absent people are accommodated in places that are machines for living in. Two images of Le Corbusier’s Salvation Army Refuge in Paris (1929) are placed vis-à-vis, all the while flanking a view of the Moscow skyline, the only trace of the outdoors in the exhibition.

Fig. 7 Interior of the Galeria Helga de Alvear (01.02.20) – Second room

Eventually the Moscow skyline, at first seemingly misplaced, would make sense.

Höfer is allowing her archive to enter into a dialogue that we are invited to listen to. Which in some ways appears ironic, because she never gave them the words to speak.

And in this manner, with the artist curating an exhibition of individual works from her oeuvre, we get to hear unspoken words.

References

Cué, E (2016) Interview with Candida Höfer. Available at https://www.alejandradeargos.com/index.php/en/all-articles/21-guests-with-art/511-interview-with-candida-hoefer [Accessed 2 February 2020]

Galeria Helga de Alvear (2019) Candida Hofer: About Structures and Colors (28.11.2019 – 08.02.2020). Available at http://helgadealvear.com/en/exhibitions/about-structures-and-colors/ [Accessed 2 February 2020]

Galerie Zander (n.d.) Candida Höfer: About the Artist. Available at https://www.galeriezander.com/en/artist/candida_hoefer/information [Accessed 2 February 2020]

Graybill, P (2007) Archiving the Collection: The Aesthetics of Space and Public Cultural Collections in Candida Höfer’s Photography. MoveableType, Vol.3, ‘From Memory to Event’, UCLPress, pp.40-70

Gueland, P (2013) Archive of Women Artists Research and Exhibitions: Candida Höfer. Translated from French by Simon Pleasance. Available at https://awarewomenartists.com/en/artiste/candida-hofer/ [Accessed 2 February 2020]

Haran, B. (2010) Homeless Houses: Classifying Walker Evans’s Photographs of Victorian Architecture. Oxford Art Journal, 33(2) June 2010, pp.189-210

Kennicott, P. (2011) Review: ‘Candida Höfer: Interior Worlds’. Available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/review-candida-Höfer-interior-worlds/2011/11/16/gIQAzMDRSN_story.html [Accessed 1 February 2020]

Soutter, L. (2018) Why Art Photography? Second edition. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-1-13828263-6

Sutherland, G. (2019) Looking for the new heroes (Berenice Abbott: Portraits of Modernity, PHotoESPAÑA 2019). Available at https://gordonsutherland.home.blog/tag/abbott/ [Accessed 2 February 2020]