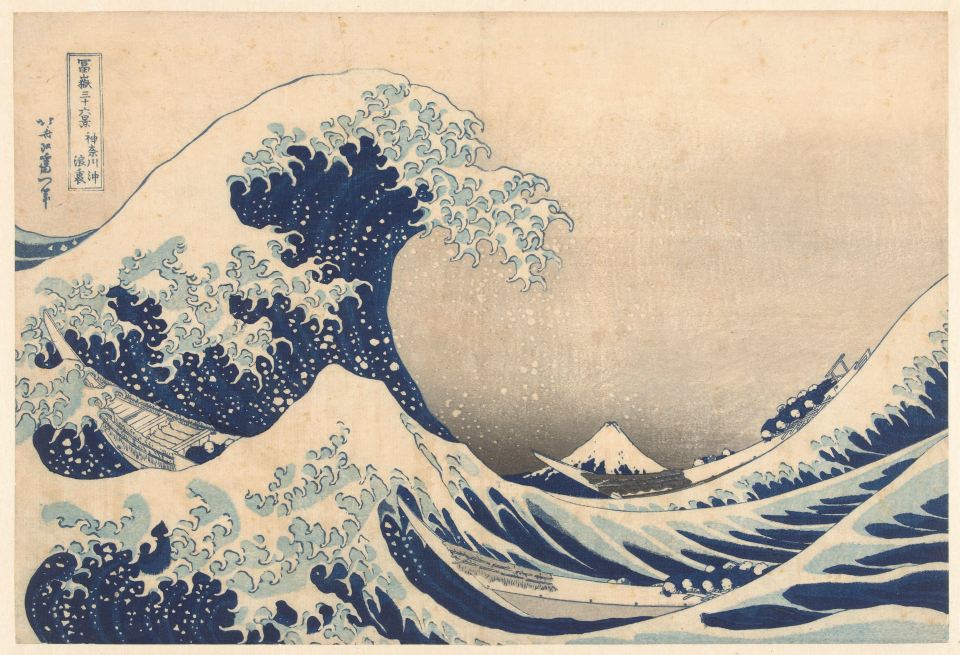

Cherry Blossom, its transient beauty embodied in the Japanese aesthetic, is correspondingly an important symbol in the country (The Art of Japan, 2017).

In the aftermath of the 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and resulting nuclear disaster in Fukushima, photographer Omori Katsumi travelled north from his residence in Urayasu towards the affected region. With his own residence in greater Tokyo not unaffected, although in the centre of the city the impact was felt to a much lesser extent, Omori felt driven – by a sense of compassion or complicity – to visit the disaster zone (The Japan Society, 2011; Fritsch 2018: 190). Along his route to Fukushima he documented the blossoming of the cherry trees.

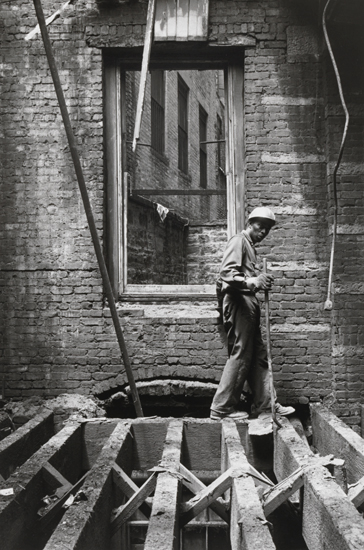

Fig. 1 Katsumi Omori, 2011, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo [59cm x 39.5cm Chromogenic Print]

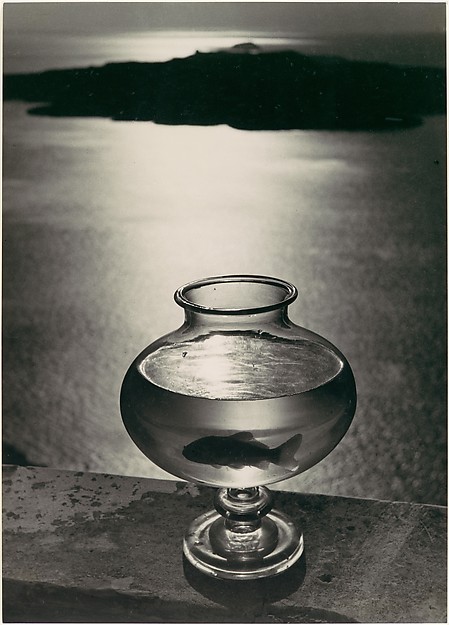

Indeed, although Omori’s home itself did not sustain much damage, the area where he lives is constructed on artificial land and some buildings were heavily impacted by the earthquake. As more information slowly became available, not even knowing exactly what he wanted to see, Omori states that he found himself wanting to go to Fukushima to witness the situation with his own eyes. Feeling that straight photography was not the way to approach this topic, he introduced a random, unrelated element (a translucent pink toy), emphasizing in this manner how we always look at things through something else, that is, through a position or a perspective (Fritsch: 189).

Omori’s documentary approach is as much frank and informal – and could be considered to emerge from new topographics – as it is subjective, opening a poetic dialogue that invites interpretation. That these images are in portrait format, in opposition to the convention for landscape photography, represents – according to Omori – ‘assertion’ in his documentary practice, with the inclusion of “some halation implying something people cannot actually see but probably exists: such as anxiety, possibly radiation or even wishes for the future” (The Japan Society, 2011).

In interviews on this series Omori regularly confirms his intention to photograph something that is invisible.

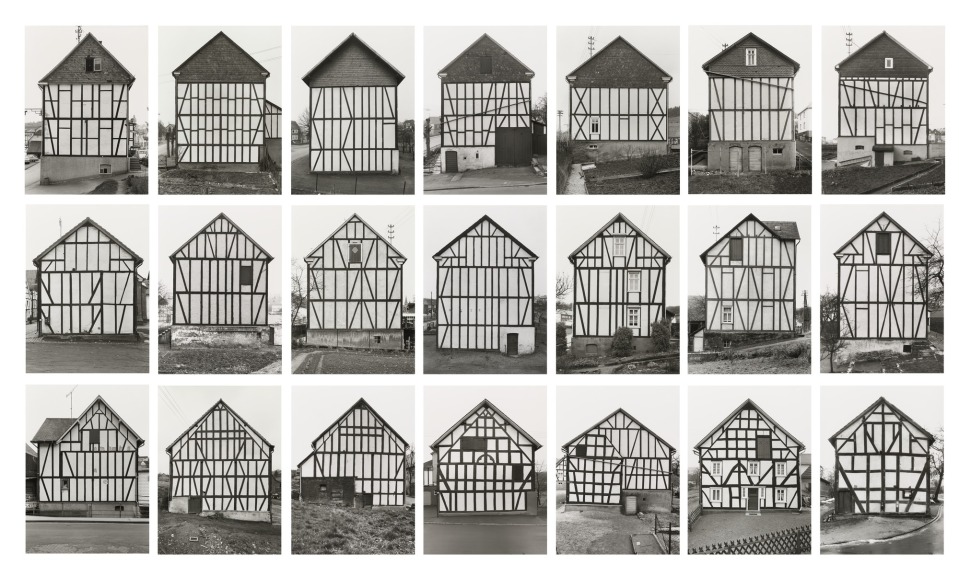

Fig. 2 Katsumi Omori, 2011, Iwaki-shi, Fukushima [59cm x 39.5cm Chromogenic Print]

“After the accident of the Fukushima nuclear plants we faced the difficulty to see, to see the world. You know, radioactivity, we couldn’t see that, so when I went to Fukushima I decided to put something, aahh [indicates ‘between the’ with gesticulation] camera and the real world” – Katsumi Omori (Opezzo 2014).

Within his photographic practice, the freezing of time is one particular element of the medium that interests Omori (Fritsch 2018: 189).

Reflecting this interest in time, and prior to the series Everything happens for the first time, Omori’s 2007 photobook Cherryblossoms had already emanated from his fascination with the symbolically fleeting nature of the blossom. Asking the viewer to consider memory in another way, for that photobook he adopted the use of tungsten film to render the blossom in a bluish tint (Shashasha 2019). However, in Everything happens for the first time, Omori proposes a new approach to the documentary of an unfolding nuclear disaster and its invisible threat.

To critically investigate the interlinked visible and invisible, the series denies transparency (What is the subject matter? What is the meaning?) through the images unconventional form and depictions of the banal quotidian in modern day Japan.

In his critical analysis, Taro Nettleton, assistant professor of art history at the Temple University Japan Campus, considers that “through their opacity Omori’s images disrupt the call to nationalism and endurance, which the Japanese government has made its official response to the disasters”. As such he places Omori’s series as an ethico-political study into societal perspectives and positioning in Japan, otherwise a study into the state projected framework of protection, control, care and normalcy within Japan’s governing system after the Fukushima disaster (Nettleton 2018: 22-23).

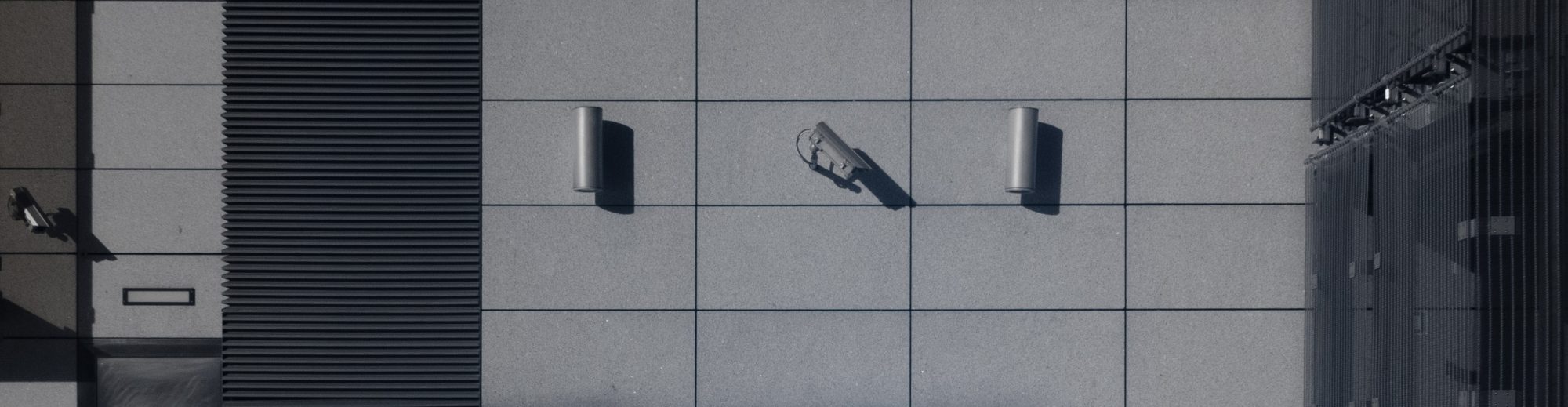

Fig. 3 Katsumi Omori, 2011, Minami Soma-shi, Fukushima [59cm x 39.5cm Chromogenic Print]

Omori‘s work, coming from a photographer who is receptive to the invisible, could further be considered as being in resonance with the popular Japanese fascination with the ethereal. His project is marked by an ambivalence “that engages with the lack of transparency in TEPCO’s [Tokyo Electric Power Company], the state’s and the media’s treatment of the nuclear disaster” (idem).

By wearing this mask of opacity, Omori’s series directly challenges the opacity of the ruling hegemony, by reminding the viewer that when we look at the world we always look at it through multi-foiled filters. Those filters may be placed over our eyes by our own government.

Omori’s fascination with the freezing of the annual regenerative power of nature, which takes place on the human scale represented by the Cherry Blossoms in Everything happens for the first time, becomes overtly more intense through the tension arising from comparison with generational timescales of the half-life of radioactive material such as the isotopes of iodine-131, cesium-134 and cesium-137 released in the Fukushima disaster. This juxtaposition is strengthened by the aesthetic beauty of the soft-pink haletic effect created by an otherwise ‘innocent’ translucent toy. On a personal level for the photographer, the hazy images appear to resonate with Omori’s own memory of the first days following the disaster, where he recalls how his “neighbourhood was covered with dust, turning everything a hazy white” and how he could barely hang on to the sensation that his body belonged to him (Omori n.d.).

In Everything happens for the first time the end result is a poignant dialogue on mankind’s futile attempts to control, and exploit, the power of nature, an effort evident in the Japanese cultural psyche, in particular in the second half of the 20th century and the first decades of the 21st, combined with an ethico-political statement on the approach of the state at the time of the Fukushima disaster.

Sources

Fritsch, L. (2018) Ravens & Red Lipstick: Japanese Photography since 1945. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-29287-7

Nettleton, T. (2018) Photographing the Invisible: Katsumi Omori’s Everything happens for the first time, Afterimage, vol. 45, no. 4, pp. 22-25.

Omori, K. (n.d.) Everything Happens for the First Time (Subete wa hajimete okoru). [Online] Available at https://www.lensculture.com/articles/katsumi-omori-everything-happens-for-the-first-time [Accessed 26 November 2018]

Opezzo, I. (2014) Paris Photo Interviews for La Stampa. [Online] Available at http://ireneopezzo.com/paris-photo-interviews/ [Accessed 2 February 2019]

Shashasha (2019) Cherryblossoms. [Online] Available at https://www.shashasha.co/en/book/cherryblossoms [Accessed 4 February 2019]

The Japan Society (2011) Everything happens for the first time Katsumi Omori. [Online] Available at https://www.japansociety.org.uk/20062/everything-happens-for-the-first-time-katsumi-omori/ [Accessed 2 February 2019]