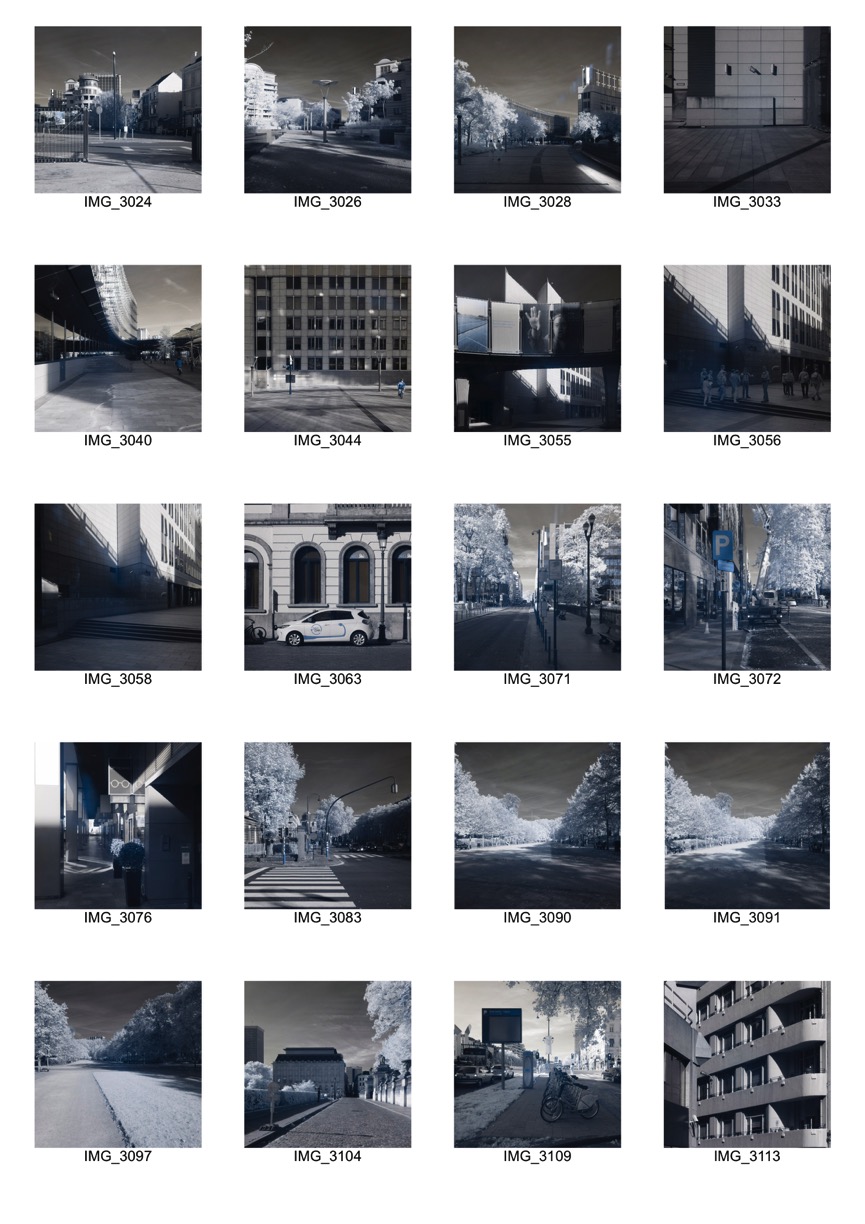

As I work towards a photography project that invites dialogue on the datasphere as an alternative space of existence, I plan to travel to Tokyo to explore the visualization of digital connectivity in one of the most densely constructed and populated megacities on the planet. My starting point is to tentatively explore Japanese culture, art and photography, and how they have been informed both domestically and by external cultures.

Japan and its culture remain an intrigue for Western Society. In the first of a three part series addressing art and aesthetics in Japanese culture (The Art of Japanese Life: Nature, 2017) the embodiment of the religious beliefs of Shintoism and Buddhism within the Japanese aesthetic are explored by art historian, and fellow at Gonville & Caius College Cambridge, Dr. James Fox (University of Cambridge, 2019).

Reflecting on the role of nature within these two religions, Fox considers that every aspect of life in Japan is driven by aesthetics. Even if Shintoism itself has not produced a legacy of art such as that emanating from the Christian religions of the West, the essence of the religion is so firmly embedded in the Japanese aesthetic that it pervades Japanese art.

The world of Shintoism is inhabited by the Kami, spirits – both good and bad – that live in everything organic and inorganic, or as Fox states, “for Shinto, the world is endlessly animated by the divine” (The Art of Japanese Life: Nature, 2017).

This concept of eternal existence is extended in Buddhism by the belief in incarnation whether as the living or inanimate, and parallels with these ancient religions can be found in contemporary philosophical studies, such as in Felix Guattari’s unfinished concept of ecosophy which would allow for a rethinking of the nature of being. A dissolution of self by becoming-other is at the heart of Guattarian (and Deleuzian) ecosophy, in opposition to an expansion of self through identification (Tinnel 2012: 359).

Just as the Japanese accept that life pervades everything, in whatever form, it is at today’s juncture of the ecological crisis and the pervasiveness of digital media associated with the information age, that a Guattarian thinking could point towards alternative domains or “transversal eco-humanities, which would be rhizomatically rooted in autopoiesis and becoming-other” (idem: 357), but “without assigning humans, nature or culture a fixed role or place in the production of subjectivity” (idem: 362). In questioning this, is Tinnel’s extension of the unfinished theory of ecosophy suggesting the possibility of existence in other form? Digital form? And how could such alternative digital spaces be visualized when we look at them through the filter of the human condition? Further, if we enter a digital space which exists only in the information age, do we become less human?

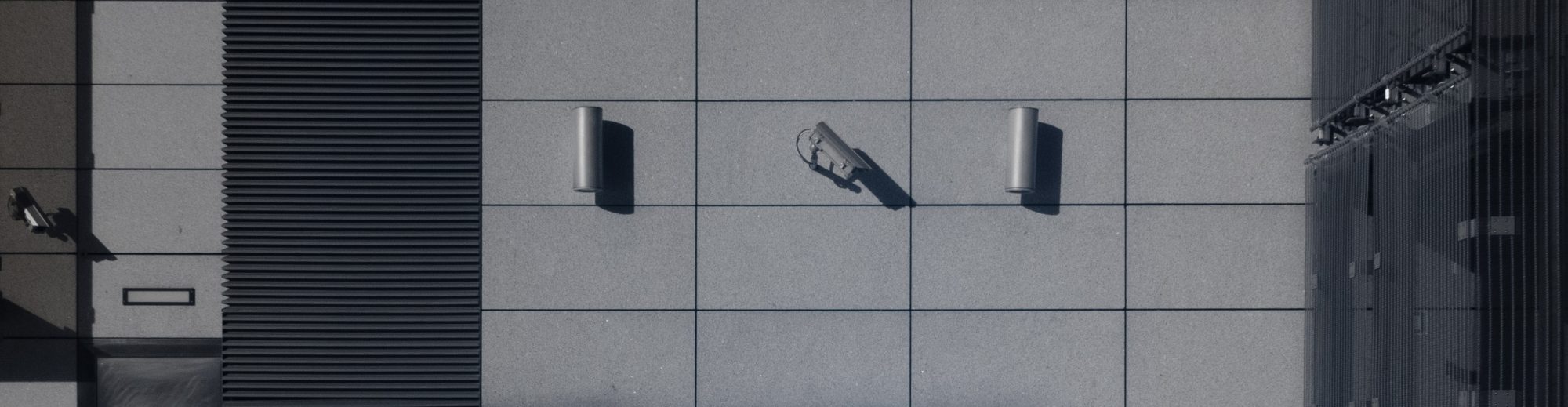

This bridge between religion and philosophy within the context of ecosophical – as opposed to ecocritical – thinking is at the heart of my visual exploration of otherness. The dominant physical infrastructure and prevalent, but juxtaposing, digital connectivity in Japan offer an avenue for photographic exploration of otherness outside of the Western media filter.

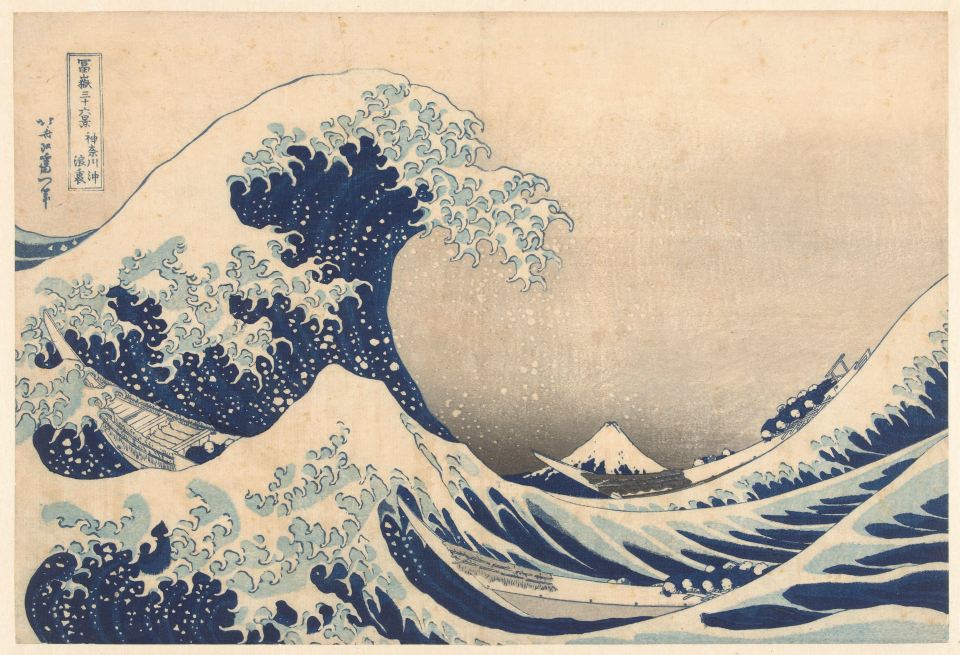

Returning then to the Japanese aesthetic, an exploration of the universal divine animation in Japanese photography would have to take as its starting point the development of the Japanese aesthetic, in particular the Japanese culture of visualization. With ‘The Splashed Ink Landscape’ (1495), Sesshū Tōyō expressed an abstraction of nature some 300-400 years before the advent of abstraction of landscape art in the west, whilst consideration of the Japanese reading of art from right to left will reveal to the uninitiated western eye insights into the semiotics of the imagery. In reading Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanugawa from right to left (Fig. 1, also know as Under the Wave off Kanagawa, Rijksmuseum n.d.), the western interpretation of the immensity of nature’s energy is revealed in Japanese culture as the immensity of life’s challenges (The Art of Japanese Life: Nature, 2017).

Fig. 1 Katsushika Hokusai, 1829-1833. Under the Wave off Kanagawa [25.4 cm x 37.5 cm, colour woodcut print on paper] (Rijksmuseum, Acquisition 1956)

It is the duality of this Japanese fascination with the fleeting, combined with a cultural drive to control nature, the outcome of which is no better represented than in the Fukushima disaster, that makes consideration of otherness through a Japanese perspective central to my work on visualizing other forms of existence in the information age.

In his consideration of the art of Japanese life Fox reflects that “in Japan nature is ignored at one’s peril” (The Art of Japanese Life: Nature, 2017). That we should ignore our own ‘nature’ through dissolution of the human condition to a digital existence is surely perilous and worthy of dialogue, visual dialogue included.

Sources

Rijksmuseum (n.d.) Under the Wave off Kanagawa. [Online]: http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.45735. Available at https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/RP-P-1956-733 [Accessed 9 February 2019]

The Art of Japanese Life: Nature (2017) BBC World, 19 January 2019. 10:10 CET. Part 1 of a series produced and directed by Ben Harding. BBC Studios, Pacific Quay Productions, Scotland.

Tinnell, J. C. (2012), Transversalising the Ecological Turn: Four Components of Félix Guattari’s Ecosophical Perspective, Edinburgh University Press, Deleuze Studies, 6.3 (2012): 357-388

University of Cambridge (2019) People: Dr James Fox MA (Cantab), MPhil, PhD. [Online] Available at https://www.hoart.cam.ac.uk/people/jf283@cam.ac.uk [Accessed 31 January 2019]