The ideas, concepts, and critical theory underpinning my initial considerations for a project investigating the nature of digital space are collated in the video The Digital Divide, an Artist Talk presenting the road to my visual voice and early research for the project.

Tag Archives: Positions & Practice PHO701

24.10.18 > Observing our digital DNA

In exploring the phenomenon of digitalisation of society I’m first of all reflecting on the nature of the digital world.

Thought experiments on Schrodinger’s unfortunate cat and developments in quantum computing aside, today’s digital world comprises of a series of zeroes and ones.

Within this digital hierarchy I’m naturally drawn to explore – for the first time in my photographic practice, other than a short undergraduate project using a Rollieflex SL66 medium format camera – images in a square format: the square format lending the photographic surface an essence of the digital DNA.

And even if the real world is not black and white, at least to our human eyes, perhaps the digital world is. So I’m also naturally drawn to explore seriously – again for the first time in a personal project – the use of black and white, or at least monotone, photographic imagery.

These are two fundamental departures from my current photographic practice, and enough to be getting on with for the time being.

Taking the square format and monotone as my creative limitations, or boundaries within which I choose to express myself, I pulled together a short series of images for informing the steps towards my Final Degree Project.

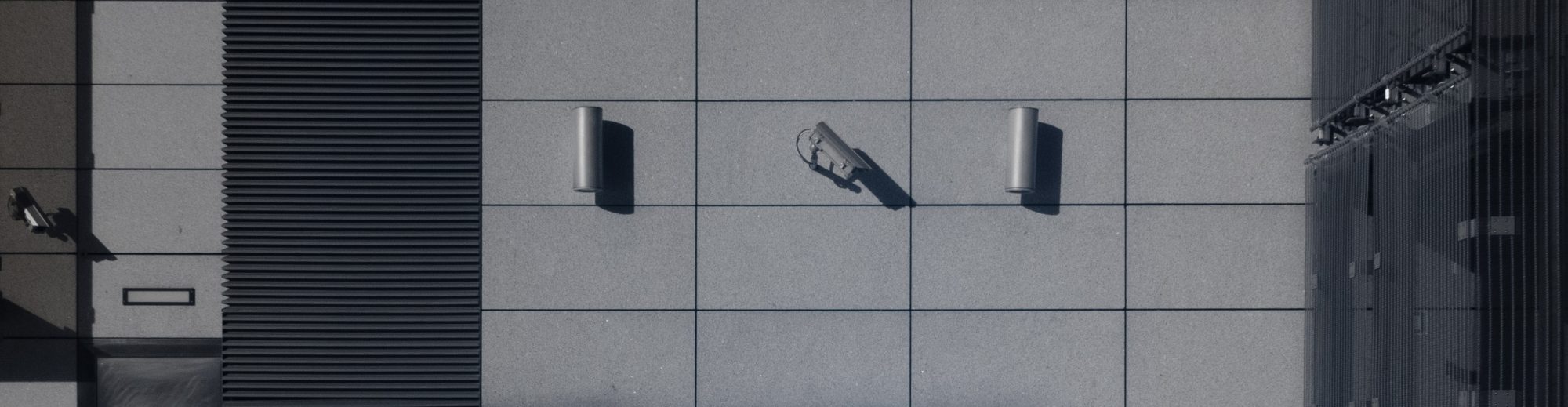

Fig. 1: Agora Simone Veil – Esplanade Solidarność 1980, European Parliament, Brussels (Image © Gordon Sutherland 2018)

Taken over one morning in and around the halls of power of the European Parliament in Brussels and the institutional district surrounding it, I feel that these locations are ideal for reflecting on power and control within the expanding datasphere. They subtly start to reveal how data flows, transmissions and surveillance are becoming omnipresent in the so-called digital transformation and start to shape the way society behaves.

Fig. 2: Esplanade Solidarność 1980, European Parliament, Brussels (Image © Gordon Sutherland 2018)

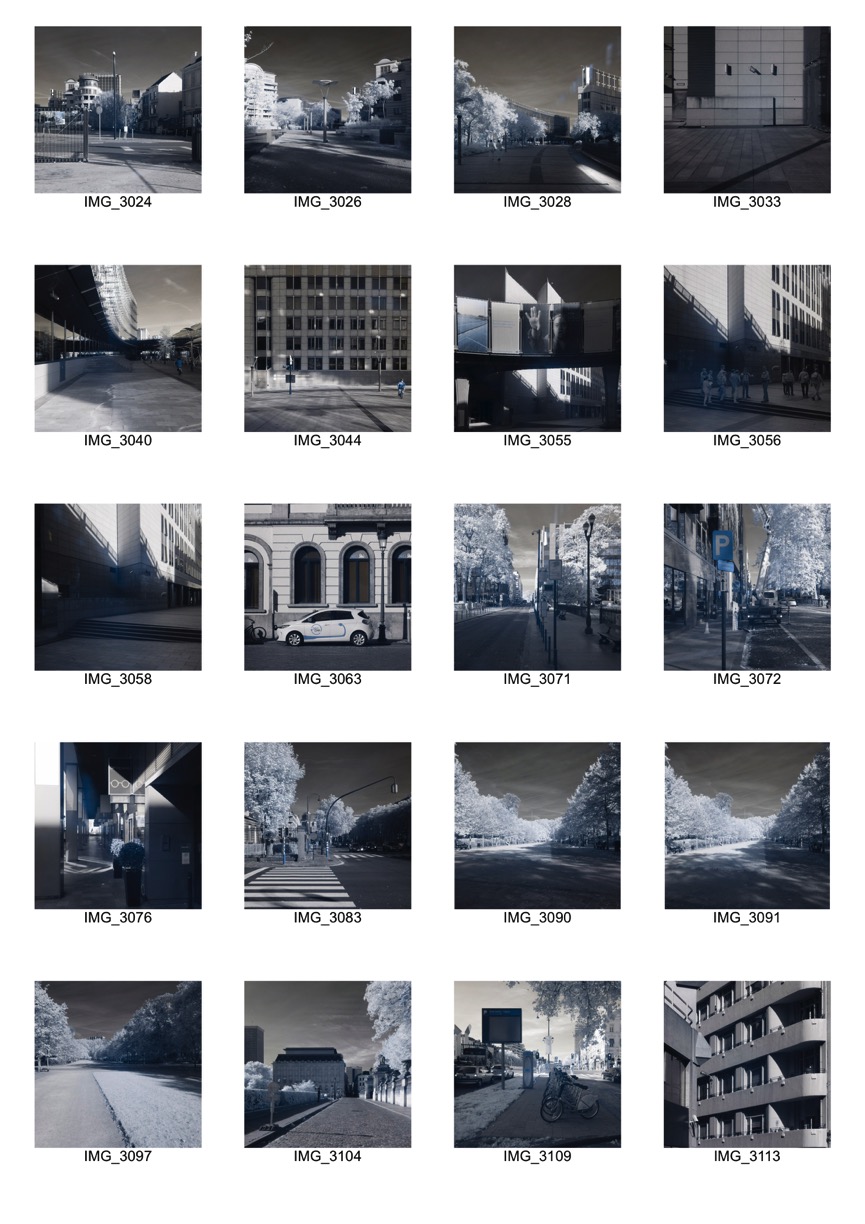

The images presented here are representative of a series of around 21 images that emerged from location scouting session and –to my mind- reveal that the square format and, in this case, monotone infrared images using a 720nm IR filter as opposed to black and white, demonstrate the futuristic feeling that I’d like to instill in the images.

Fig. 3: A short portfolio of images informing the development of a proposal for the Final Degree Project, Brussels, Saturday 13 October 2018 (Image © Gordon Sutherland 2018)

What is our digital future? What shape does it take? Is it a habitable space? – these are perhaps the emerging questions I’d like to raise in the mind of the viewer of my images.

Looking at these images, although they form part of a development process, they sit as a finished portfolio, a portfolio of developmental sketches for an emerging project.

Fig. 4: Parc de Bruxelles – Brussels Park, Brussels (Image © Gordon Sutherland 2018)

As with my previous projects they may frame and accompany the final project until its completion.

The questions thrown up by these images revolve around inclusion, or not, of people in the final set of images. And if so, how to include people, other than the viewer, within the image? Staged, or random street photography?

On the other hand, I’m wondering if people actually live in the digital world, so perhaps their complete absence from the images would magnify that enquiry?

23.10.18 > Surveillant or surveyed? – Photography, the double agent

The idea of the datasphere as existential space is the main avenue of current exploration for my Final Degree Project.

The datasphere is considered as the “notional environment in which digital data is stored” as well as “the space of virtual reality, or cyberspace” (Oxford Dictionaries 2018).

My thematic direction for this project remains open, my initial considerations lying in identifying how a space as invisible as the datasphere can be visualized.

Where do people, individually or collectively, enter into, or interact with, the datasphere? Can those portals be associated with visual markers? How much of the human condition is lost through interaction with, and habitation within, a digitalized world?

Fig. 1: Sunday, October 7th 2018 in Place Eugene Flagey, Brussels, Belgium (Image © Gordon Sutherland 2018)

Musings on surveillance, propaganda and societal control by the gatekeepers to the datasphere and considerations around policing of cyberspace point to potential literary and visual texts as inspiration: Orwell’s Nineteen Eight Four, the Wachowskis’ The Matrix, and Toffler’s Future Shock, for example. How much information can a society absorb before it suffers from culture shock within its own culture?

But where is this digital world and is it tangible enough to be visualised? How is it changing society?

A recent Pew Research study in the United States shows that teens are trying to find the balance between the anxiety of spending too much time on their mobile phone against the worry they feel when they are separated from it (Tiku 2018). Whilst the youngsters involved reveal that they are taking steps to limit the time they spend on their phones, these efforts aren’t necessarily making them happier. Over fifty-five percent of American teens have feelings of anxiety and loneliness – or felt upset – when they are away from their mobile phone.

The report states that American parents also struggle with similar issues in relation to screen time, sometimes to a greater extent. Thirty-nine percent of parents admit to often or sometimes losing focus at work when looking at their mobile phone, this in comparison to the thirty-one percent of teens who state to having lost focus during class time for the same reason. Further, fifty-one percent of teens say that whilst trying to have a conversation with their parent or caregiver, the other person has been distracted by mobile use.

The layers of digital invasiveness in day-to-day life are not only from mobile phones, but come in the form of notifications through various media. These notifications shape the way we live and respond to those around us. I find myself wondering what would happen if the notifications stopped? How would a contemporary digital society respond without these signals?

The 2014/15 exhibition “Watching You, Watching Me” at the Open Society office in New York featured the work of nine visual artists documenting and exploring the surveillance and data retention activities of governments, corporations, and individuals. The exhibition explored not only how photography has been used as much to challenge the practices of surveillance as it has itself been an instrument of surveillance.

Of interest for further research is the work of Edu Bayer for the New York Times in 2011 in which he documented the surveillance apparatus of Colonel Muammar al-Qaddafi’s regime, the headquarters of which were housed in a six-story building from which citizen’s movements and correspondence was monitored (Bayer n.d.). The work can be viewed in the context of ‘the ruin’, exposing surveillance in its aftermath.

In his work ‘Plain Sight: The Visual Vernacular of NYPD Surveillance’, aka profiling.is, Josh Begley uses Associated Press released visual texts to produce a wall of images from the NYPD’s surveillance of institutions of businesses affiliated to the Muslim faith. In this project the data artist, filmmaker, and app developer Begley draws attention to the scale of photography’s role in state apparatus surveillance activities. The wall of surveillance material makes me think of a massive contact sheet. Taken more subtly, reference can be found in the display approach of Bernd and Hilla Becher.

Over two years, Simon Menner had access to the Stasi’s visual legacy archived by the Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Archives of the former German Democratic Republic. Menner’s presentation of the images allows reflection on the use of photography as a tool at the service of the secret police, whether for training secret service agents, conduction of clandestine home searches, or to track people’s movements (Yamagata 2014). Menner states “They concern photographic records of the repression exerted by the state to subdue its own citizens. For me, the banality of some of these pictures makes them even more repulsive.” (Menner 2018). He further reflects that many of the images are fully open to interpretation making them susceptible to attribution of meaning according to the suspicions of the secret service.

Perhaps the discourse around surveillance, truth, and the (mis)use of data is not too distant from the broader photographic debates of subjectivity and objectivity, or discussions on the fundamentals of intertextuality between visual and written texts. What is the true reading of a photograph in the absence of corroborated written or recorded texts?

The idea of photography as a double agent, or perhaps simply the devil’s advocate, arises in the discourse around its capacity to awaken social conscience of the role that surveillance and state control play with regards to fundamental rights and civil liberties. The ubiquitous nature of the ‘connected’ camera phone and tethered or wi-fi enabled DSLRs means that in both citizen documentary and professional photojournalism, photographers are as much capturing images of socio-political concern with a view to informing the viewing public, as they are providing evidence for use by the surveillance apparatus of the state and other organisations, real or virtual.

The philosophical question remains: is virtual also real? And what does photography the double agent have to say in this debate?

Endnote

Whilst reflecting on surveillance in the data age I was listening to the soundtrack from the film Good Bye Lenin!. The music recalled the story of the fabricated reality created by a young man to protect his mother from shock after she awakes in 1990 from a long coma, to prevent her from learning that the nation of East Germany that she knew and loved had disappeared, and together with it much of her identity [Yann Tiersen 2003].

Sources

Bayer, E. (2018) Gadhaffi Intelligence Room. Available at https://edubayer.photoshelter.com/index/G0000nniWlU_S9oM [Accessed 22 October 2018]

Begley, J. (n.d.) The visual vernacular of NYPD surveillance. Available at https://joshbegley.com/ [Accessed 22 October 2018]

Menner, S. (2018) Images from the Secret Stasi Archives

or: what does Big Brother see, while he is watching? Available at https://simonmenner.com/_sites/SurveillanceComplex/StasiImages/_StasiImagesMenue.html [Accessed 22 October 2018]

Oxford Dictionaries (2018) Definition of datasphere in English. Available at https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/datasphere [Accessed 21 October 2018]

Tiku, N. (2018) Even teens worry that teens are addicted to their phones. Available at https://www.wired.com/story/even-teens-worry-that-teens-are-addicted-to-their-phones/ [Accessed 21 October 2018]

Yamagata, Y. (2014) Taking a closer look at surveillance culture through photography. Available at https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/voices/taking-closer-look-surveillance-culture-through-photography [Accessed 22 October 2018]

Musical inspiration

YANN TIERSEN, 2003. Good Bye Lenin! [CD]. 7243 5 82548 2 2. Labels

20.10.18 > The global image

Fig. 1: Students participate in a photography summer school at Central St. Martins – University of Arts London (August 2018)

The global image is all around us: ubiquitous and pervasive. We are bombarded by images. Try walking down the street consciously ignoring every image that you see. Make an effort to delete them from your field of vision. The world quickly becomes uncluttered. It seems that the still image is everywhere, pushed aside only by the multitude of moving images that steal our attention, pulling us in through a kind of animal instinct that focuses on movement.

To continue to gain our attention the global image stretches the boundaries of cultural acceptance before becoming banal or mundane. An alien browsing photographic archives of personal photographies in the second decade of the 21st Century on planet Earth might be excused for thinking that we are a profoundly communal species sharing moments by peering out of digital slices of time, whether to express, to consume, or perhaps to be consumed. Like fledglings in a nest consciously, or unconsciously, needing to attract attention to survive in a competitive world.

The boundaries of photographic representation once determined, they become the quotidien acceptance of the global image as an unconscious representation of society today. And so the next step in pushing the boundary of photographic representation must arrive and photographies evolve further: continuously flexible temporal networks, or interconnected systems, which interlink visual representations of space, time, reality, imagination and the human condition.

When everything has been photographed what is there left for photographers to do? I remember wanting to visit an exhibition at the Pompidou Centre a few years back, which explored the concept of there being nothing left to photograph. The queue was too long, so I’ve been left with my own thoughts on the possibilities that remain for photography now. Are they endless?

The pervasive nature of photography is not a new phenomenon. Hand (2012) informs us that “the New York Times ran a story in 1884 concerning an ‘epidemic’ of cameras, with amateurs described as ‘camera lunatics’ training their cameras simply on those walking down the street” (Hand: 4). The sociological response to this was similar to today’s concerns about privacy, invasiveness, decency and the breakdown of societal norms.

In the image above a photographer takes an image of photographers talking about photography: this allows for humorous or iconic discourse, revealing aspects of today’s version of this lunacy (Fig. 1: Sutherland 2018).

In another instant, the photographer ‘steals’ a moment of someone sleeping, a private moment in which the person is disconnected from self-consciousness, captured consciously by a photographer using an optical instrument which records unconsciously (Fig. 2: G. Sutherland 2018).

Fig. 2: Sleeping visitor in the National Theatre, Southbank, London represented in IR 590nm post-processed to black & white (August 2018)

Reflecting on my place within the concept of the global image, I again recall lyrics from Coastguard by British Sea Power: “We’re all in it, we’re all in it, we’re all in it and we close our eyes” (British Sea Power 2013).

It seems inherent to photographies as visual expressions of personal or cultural world-views that they concern the boundaries of the socially acceptable. Photographic images have the ability to grab attention, when the written or spoken word can’t be heard above the voices of others. It could be that what is stated visually, has more potency than written language, albeit with less clarity. Perhaps this is because of its ambiguity?

In photographic practice I’m increasingly challenged to remake any image brought into the photographic realm, or saturated as Walter Benjamin would have stated it, from amongst all the concepts of images in the minds of a world of photographers. That said, it can make sense to look at new light through old windows, or to project new considerations of old stories in the light of the (digital) age in which we now live. Times have changed and so have the interpretations.

Fig. 3: Art gallery visitors in the Tate Modern Turbine Hall represented in IR 590nm (August 2018)

The question remains: is there anything new under the sun to photograph? And will it remain ‘new’ once it has come into existence from its previous existence as an idea ready to become a photograph?

For the most part, commercial and art photography today sit both within and aside of the realm of digital photography, which in itself is a sub-culture of digital culture. They sit within it when they conform to its norms, they sit apart when they are breaking those norms. Yet, once they break the norms, they become part of the norm. “The Shape of Light” abstract photography exhibition at the Tate Modern in 2018 was an example of a critically acclaimed and publicly accessible photography exhibition which demonstrated how photography has taken its place with other arts, on a mass scale, as art for awakening conscience and art for consumption (Fig.3: G. Sutherland 2018).

The other part of this sub-culture is personal photography and together they reveal everyday photographic practices, whether production or consumption, which in “contemporary Western cultures involve unprecedented levels of visual mediation” (Hand: 3). Even analogue or alternative photographies rely on digital distribution and consumption, clearly placing photography as a part of today’s digital society.

For my part I interpret the concept of the global image ontologically as the current culture of production and distribution of images through which they pervade every aspect of our life, whether as personal or professional photographies. Photographic image has become an intrinsic part of our existence.

Sources

BRITISH SEA POWER, 2013. Coastguard. In: From the sea to the land beyond [Vinyl]. RTTRDLP679. Rough Trade Records.

Hand, M. (2012) Ubiquitous Photography. Cambridge: Polity Press. ISBN-978-0-7456-4715-9