Berenice Abbott recorded the evolution of the New York cityscape in the 1920s and 1930s century as it morphed into a scaling metropolis. During this period New York was synonymous with modernism and the new understanding of urbanism and architecture.

Fig 1: Outside the Fundacion MAPFRE

Oft named a successor to the documentary tradition of Eugène Atget, before her architectural oeuvre Abbott also did portraiture of the intellectual avant-garde during her time in Paris. It was at this time that she met, and learned of the work of, Atget. Abbott’s work straddled the Atlantic, maintaining connections between the old world and the new.

This exhibition covers her portraiture work, her documentation of New York and her later – more experimental – scientific photography, as well as being accompanied by a series of images of Atget (PHotoESPAÑA 2019).

The exhibition is curated along these three bodies of work, in chronological order, interspersed by the Atget gallery, which allows transition into the gallery with the comparatively more understated images of shop frontages. Of particular interest, and effect, was the positioning of images of construction of the Rockefeller Building vis-à-vis those of the squalor which existed in the city following the Great Depression. Also visually effective was the transition from the modernist city of infrastructure, mass transit and automation, with the scientific photography of the 1950s.

Fig. 2 Exhibition Layout, Surfaces & Strategies Workbook excerpt 16.06.19

In her essay Berenice Abbott: In-Between Visualities, the exhibition curator Estrella de Diego takes as her starting point Abbott’s two portraits of Eugène Atget, considers these images as being similar to documentary mug shots. She compares Abbott’s revisiting of this approach in portraiture, but with such diverse angles that each angle reveals the uniqueness and diversity of each individual, rather than placing them in a taxonomy, reflecting on the drive behind the nineteenth century archival approach as a mask for control (de Diego 2019: 11).

Although the exhibition includes 11 images by Atget, in my photographer’s response to this exhibition I felt disinclined to focus on the mutuality of the relationship between the two photographers, focusing rather on those aspects of Abbott’s work which inform my own gaze, namely looking at the transitory nature of existential space from different perspectives. My starting point of response is therefore exactly the same as that of the curator, although I took my own path as my reading of the exhibition and the oeuvre as a whole is influenced by what I bring with me!

I can relate to de Diego’s consideration that “[concerning Abbott] … when taking a photograph: the character, the building, the scene documented become part of her own life by virtue of her being there and looking on as she records the image. She was there; the story has been absorbed in her own biography.” (idem: 12).

My own images are at once documentary, or preservation, photography, as much as they are constructed stages where the individual and distinct – though sometimes overlapping – narratives of both the author and the reader of the visual text take place.

Portraiture

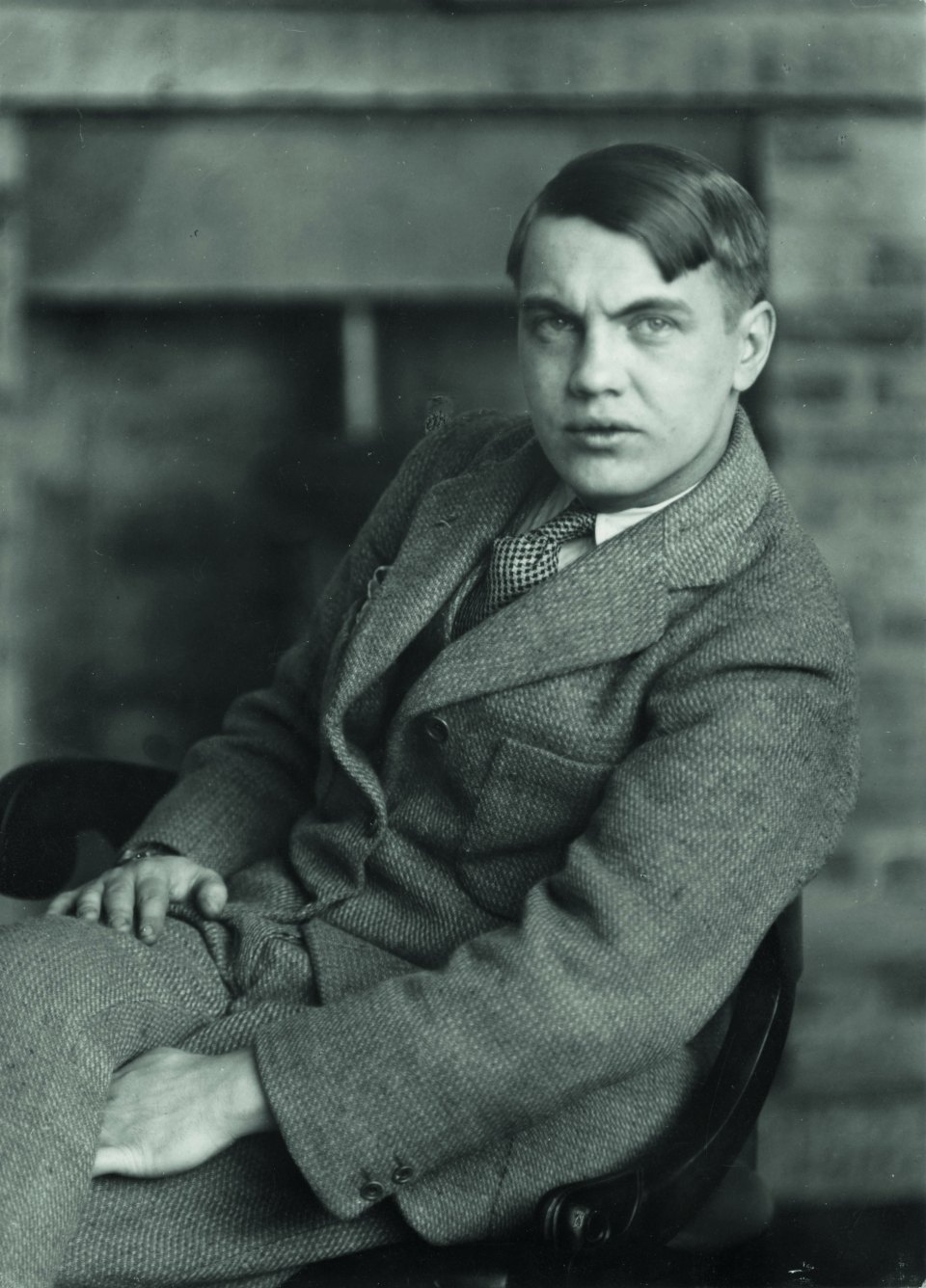

It is clear, following de Diego, that in the case of Abbott “her distinctive photographs function as a privileged archive of the avant-garde and its pioneers”. In other words, they are portraits of the new heroes, such that the images constitute “posterity before posterity itself” (idem: 13).

Fig. 3 The ‘new men’ & ‘new women’, Surfaces & Strategies Workbook excerpt 16.06.19

My own, no doubt coloured, reading of Abbott’s portrait photography is that the subjects have a distinct air of knowledge that things are not going to stay the same forever.

Fig. 4 Berenice Abbott, 1927. George Antheil

Abbott’s portraits constitute a gaze of modernity, emerging in the late 1920s and early 1930s. What is captured is the diversity in society that would only become truly established at the end of the 20th century, Afro-Americans, feminists, homosexuals, and ‘new-men’ (today coined metrosexuals and revealed by Abbott’s images as willingly ‘fragile’, or sensitive), each liberated to be who they are, and who they want to be, in society (idem: 23).

Further, de Diego considers that the portraits as having a “family air that recalls the fabulous archives of Andy Warhol’s polaroid portraits” (idem: 15).

I would posit that the similarities are to be found in the stance of the photographer both as one of, and being amongst, the new heroes. In the case of Warhol, this is the avant-garde of almost the entire latter half of the 20th Century.

Indeed, in the words of Warhol, “The United States has a habit of making heroes out of anything and anybody, which is great” (Golden 2017: 249).

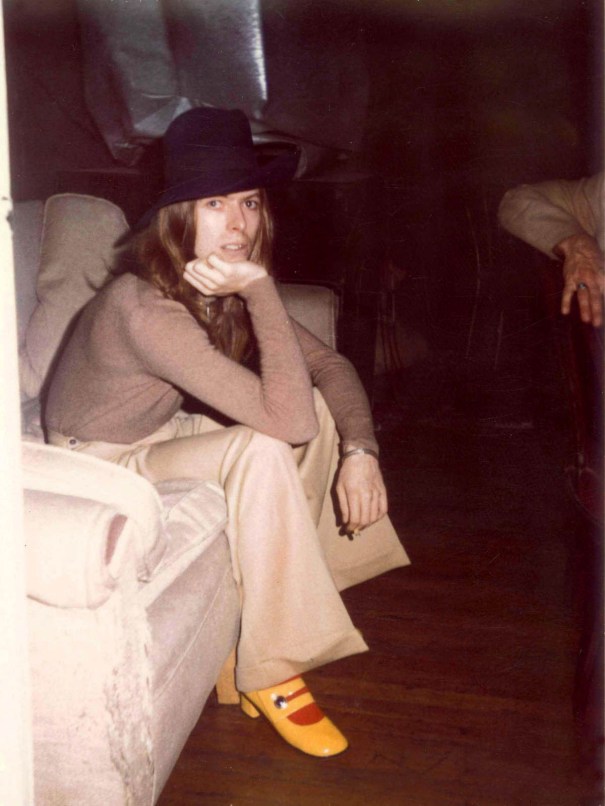

Fig. 5: Andy Warhol, 1971. David Bowie. (Golden 2017)

Changing New York

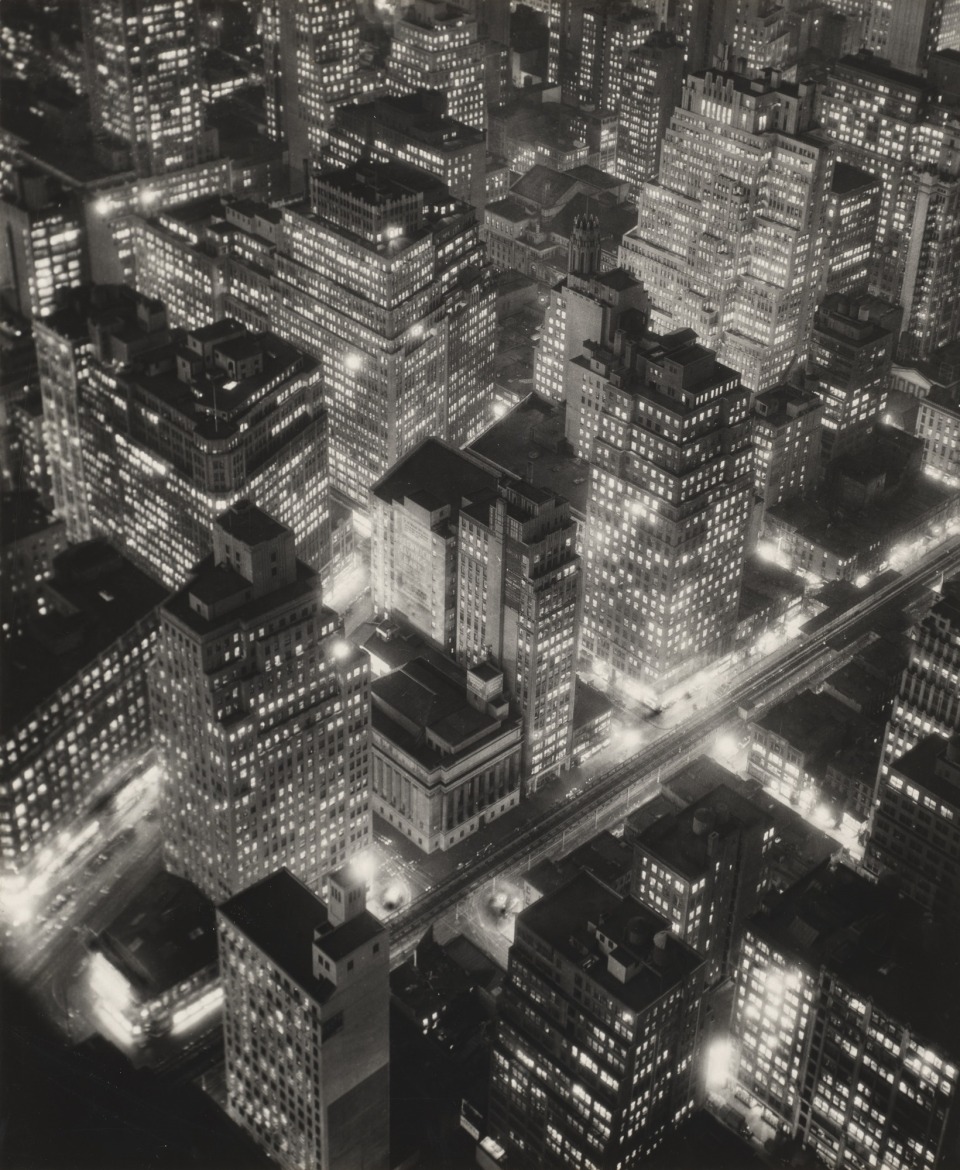

When it comes to a portrait of a city, de Diego states that Abbott’s “images of New York anticipate the monumental nature of the architecture of the new cities” considering her as the undisputed master of skillful and poetic photographic portrayal of these buildings as the new structural heroes of their time (de Diego 2019: 15). In New York, after de Diego, Abbott constructs the biography of a metropolis “almost before it has taken shape”.

It could be counter argued that – as opposed to capturing posterity before posterity – this is simple enough to state in hindsight, when documentary images can be curated to tell the story of how society arrived at its present status-quo.

Nevertheless, it is the timing of Abbott’s body of work that is compelling. New York was in transition and Abbott chose the city as her subject at that time. This is the approach to take to be avant-garde in documentary or preservation photography: your subject matter has to be avant-garde, or situated in an avant-garde context, at which point in time, as de Diego quotes Terri Weissmen, it is possible to capture “a moment or a manifestation of cultural transformation” (idem: 15).

Through alternative perspectives, Abbott’s images reveal distinct New Yorks – the city climbing to the heavens and the earthly activities that take place at ground level. Or, as de Diego comments, her images are characterized by the “dissociation between the two, the stage curtain and the floor”.

Tellingly, de Diego parallels Abbott’s portraits of people at the time of societal transition with her portrait of a city transitioning into modernity, “Just as she strips bare the essence of her sitters in each of her photographs, despite the lack of components and order required by an archive, Abbott extracts the pieces used used to assemble a city on the brink of existing and isolates them” (idem: 16).

Points of view

According to de Diego, Abbott does more than document New York, rather she documents the city from her own position as a woman breaking through the walls of the patriarchal society, stepping into her emancipation, “free to transgress what is expected of her”. In doing so she creates her own life story (idem: 18).

Abbott has the eye of modernity, because she is herself one of the new heroes of that emerging modernity. Much of the early work she did in New York prior to 1935 was self-financed, until she received a contract from the Federal Art Project which would allow her to focus on documenting the city’s transformation, leading finally to the 1936 exhibition Changing New York (idem: 18).

Nevertheless, Abbott’s New York would continue to change after her work was done. The transitory nature of the cityscape and city life which it stages, is well documented by Abbott’s House of the Modern Age, Park Avenue & 39th Street (13 October 1936), which existed only for a few months, and for which aspiring New Yorkers visited to view its mod-cons (Smith: 31).

Fig. 6: Berenice Abbott, 1936. House of the Modern Age, Park Avenue & 39th Street (Smith 2011)

Formally and compositionally different, but contextually similar, Abbott’s perspective in House of the Modern Age resonates with Walker Evans’ 1931-33 series of Victorian Houses, even as the “future of the American single-family house looked less like Abbott’s image than like William Garnett’s view of a gigantic development some twenty years later” (idem: 33).

Fig. 7: William A. Garnett, 1953-56. Housing Development, San Francisco, California (Smith 2011)

Abbott’s image (Fig. 6) again captures posterity before posterity, just at that moment when skyscrapers were becoming the only financially tenable option in midtown New York. Similarly, Evans’ images of Victorian houses ultimately reveal social fissures through abstraction, by approaching the depression indirectly through adoption of an archival stance of hyper realistic depictions of buildings which were about to disappear (Haran 2010).

Although, according to Baldwin (2013), Abbott photographed much of New York in a manner usually as understated as that of Atget, much of the work is also celebratory of the emerging metropolis. Her series Changing New York jumps from one mode of seeing to another, from atop skyscrapers to below bridges, to straight photography of shop-fronts, making the work a dizzying document of a city under constant construction.

Fig. 8: Berenice Abbott, c. 1932. The West Side, Looking North from the Upper 30s.

By 1939 Abbott’s radical visual poetry was already being watered down, as the publishing house E.P. Dutton & Co. selected 97 images of the city in the format of a guide, releasing it without the inclusion of images of the poorest and most deprived parts of the city, nor with the captions penned by Elizabeth McCausland (de Diego 2019: 18).

The city’s continuous transformation – if not so much through its cityscape as through its cultural transformation, would be documented by later photographers – the next generations of heroes – such as William Klein, Joel Meyerowitz, not to mention artists such as Andy Warhol.

Returning to the start, with Atget, de Diego posits that “Abbott was fascinated by Atget as a witness of his time. Perhaps it was from him that she learned about the autobiographical involvement required by all documentary photographers, and how one must look with one’s whole being in order to capture a reality that is always partial, always a half-truth” (idem: 20) and asks if all documentary work is not, finally, “an autobiographical experience for the photographer taking the photo?”

If so, how should the works of Abbott, Atget, and others be read in relation to documentary, autobiographical stance, and the concept of the photograph as a stage and performance (idem: p21).

In the context of that question, de Diego posits that Abbott’s portrait of New York is a self-portrait of the photographer’s own liberty.

Fig. 9: Berenice Abbott, 1935. Daily News Building, 42nd Street between 2nd and 3rd Avenues, Manhattan

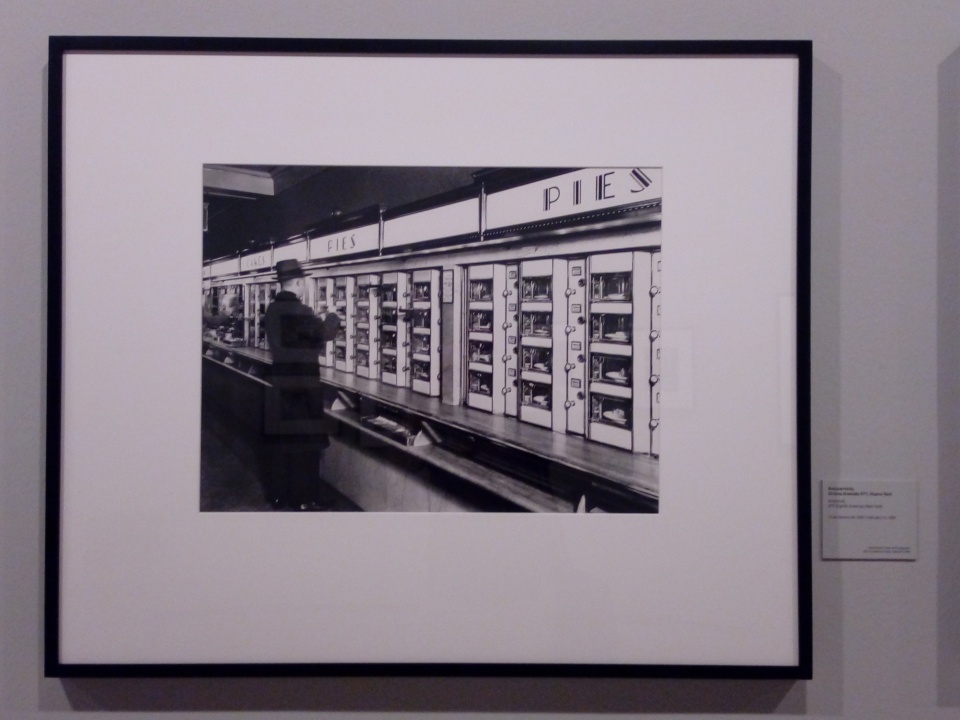

Fig. 10: Berenice Abbott, 1936. Automat, 977 8th Avenue, New York (Image from the exhibition)

Sources

Baldwin, G. (2013) Architecture in Photographs. Los Angeles: Getty Publications. ISBN 978-1-60606-152-7

de Diego, E. (2019) Berenice Abbott: In-Between Visualities. In: Davies, D. M. (ed.) Berenice Abbott – Portraits of Modernity. Madrid: Fundación MAPFRE. ISBN 978-84-9844-704-0

Golden, R. (Ed.) (2017) ANDY WARHOL Polaroids 1958-1987. Cologne: TASCHEN. ISBN 978-3-8365-6938-5

Haran, B. (2010) Homeless Houses: Classifying Walker Evans’s Photographs of Victorian Architecture. Oxford Art Journal, 33(2) June 2010, pp.189-210

PHotoESPAÑA 2019 (2019) Berenice Abbott – Portraits of Modernity. Available at http://www.phe.es/en/exhibition/berenice-abbott-portraits-modernity/ [Accessed 10 June 2019]

Smith, J. (2011) The Life and Death of Buildings: On Photography and Time. Princeton University Art Museum. Yale University Press. New Haven and London. ISBN 978-0-300-17435-9