Foreword

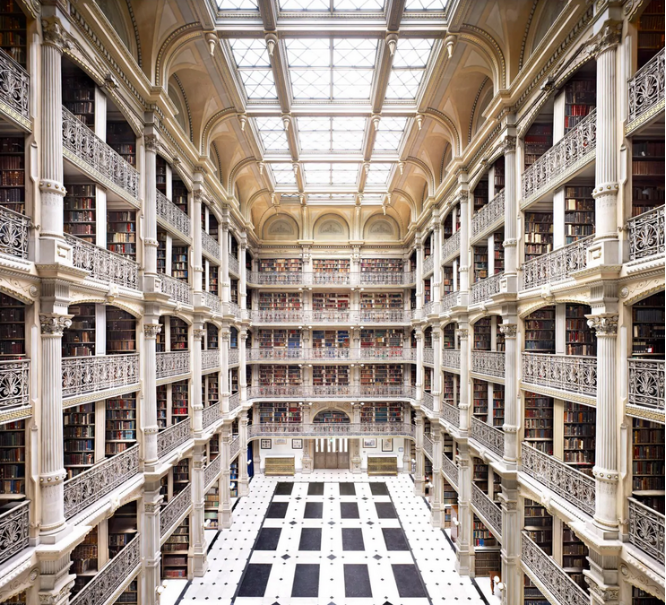

In 2019 during my visit to the exhibition ‘Framed Landscapes: European Photography Commissions 1984-2019’ at the Fundación ICO in Madrid, I picked up a copy of the essay ‘Not to occupy a place, but to create space’, by museum director and curator Kasper König (König 2005).

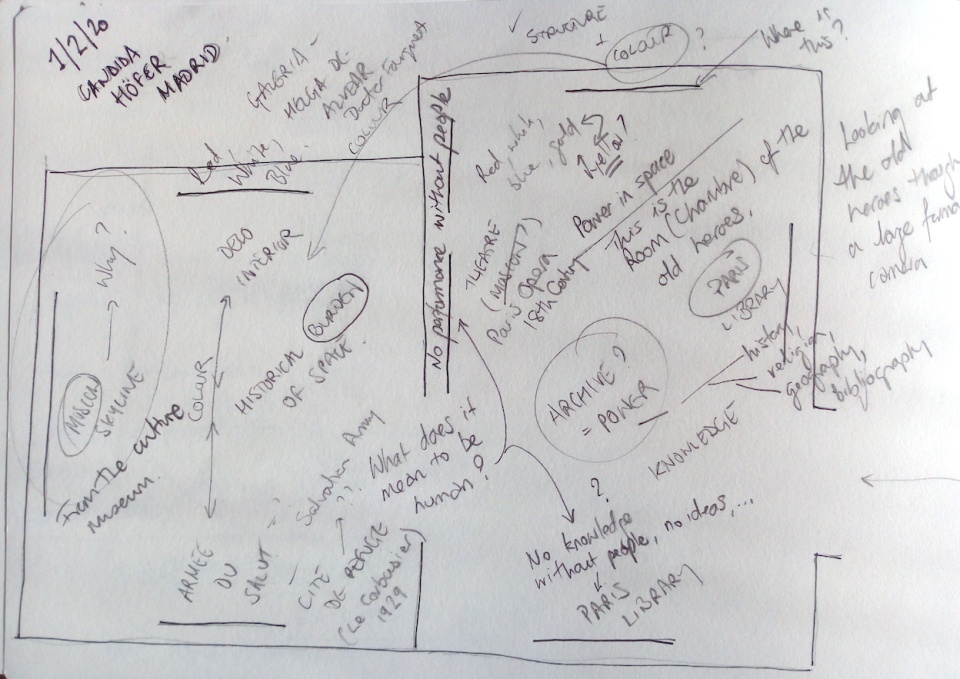

Although this is an essay on sculpture, I could feel it resonating with my thoughts on how to visualize non-physical space – the subject matter I’ve been contemplating throughout my Master’s degree – as well as how I might approach my elusive and constantly evolving Final Major Project.

The Framed Landscapes exhibition was pivotal in revealing that my project could be something more than its photographic representation, its photographic existence. While writing this entry in my Critical Research Journal I’m still not sure what that ‘something more’ is.

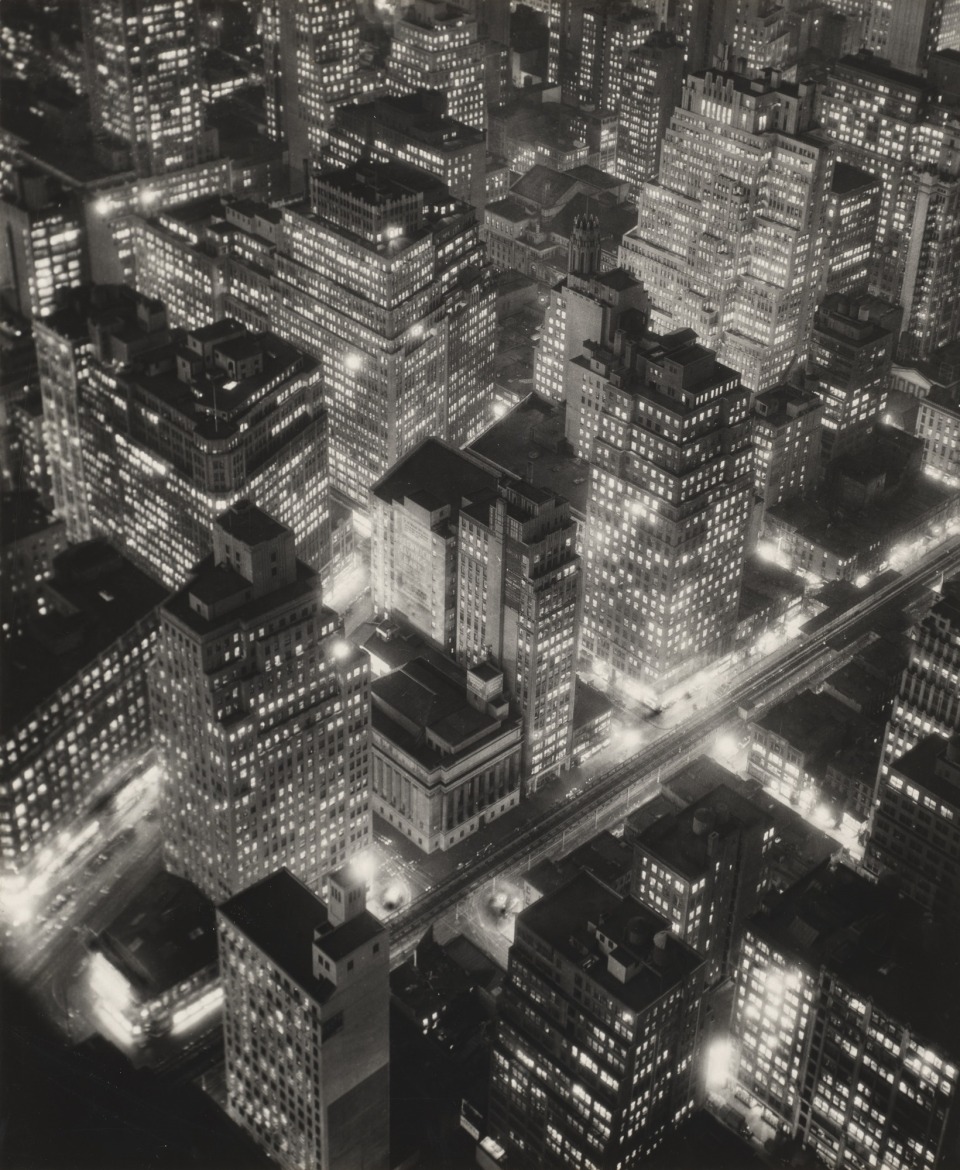

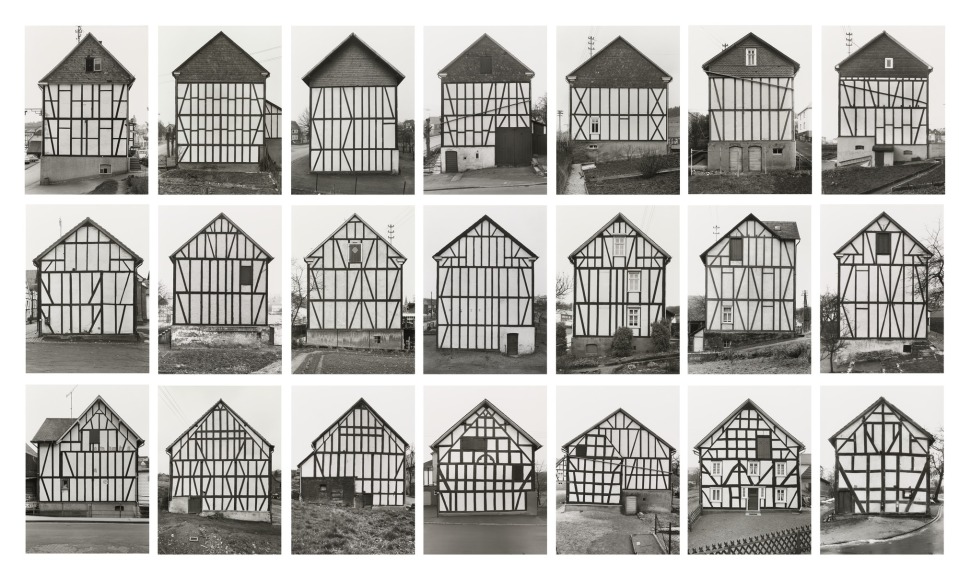

One of the projects on display in the exhibition, the photographic commission Schlieren: Spatial Transformation in a Suburban Municipality in Switzerland (Fig.1) by Meret Wandeler and Ulrich Görlich, is a collaborative study of transformation in one specific community over nine years (Wandeler 2019). Indeed, Wandeler’s serial projects are characterized by the fact that the research constitutes the project, and not the photographs per se (Sutherland 2019).

Fig. 1. Meret Wandeler/Ulrich Görlich, 2005, Elmar Mauch (Rephotography) 2007, Christian Schwager (Rephotography) 2009–2017, Example of overviews from ‘Long-Term Photographic Observation of Schlieren 2005-2020’ (Wandeler 2019)

This month, in search of the heart of my project and answers to my questions about space, I took König’s essay from my bookshelf.

Not to occupy a place, but to create space

Whilst reading König’s essay ‘Not to occupy a place, but to create space’ – which reflects on the 1977, 1987, 1997 and 2007 (at that time still to be realised) editions of the Münster Sculpture Project – I found myself wondering about the concept of space as a three-dimensional volume.

Or rather, I started wondering about our apparent preoccupation with space as something which exists in three dimensions.

Indeed, Tate defines sculpture as an art term for “three-dimensional art made by one of four basic processes: carving, modelling, casting, constructing” (Tate n.d.).

Yet ‘space’ doesn’t necessarily have a physical dimension, such as in ‘head-space’ or ‘cyberpsace’, whilst in photography it is represented on a two-dimensional surface.

The question arises, if space doesn’t necessarily have a dimension, what is actually being represented in a photograph?

The Münster Sculpture Project is a city art project including outdoor installations, – mainly, but not exclusively – temporary, spread across the city’s public spaces.

In exploring the art works, König indirectly reveals that each of the artists identifies an elementary, or fundamental, characteristic of the place and then creates a space which represents that.

On Untitled (Fig.2), Donald Judd’s work for Münster, König reveals that the place offered Judd the opportunity to realise an idea that he’d been considering for a while.

Fig. 2 Donald Judd, 1976/77, Untitled, Lake Aa meadows below Mühlenhof open-air museum, Münster, 51°56’59.3″N 7°36’04.8″E. [Outer ring: height 0.9 m, width 0.6 m, diameter 15 m, Inner ring: height rising from 0.9 m to 2.1 m, width 0.6 m, diameter 13.5 m, Concrete sculpture] (Public collection of Stadt Münster) Photo: LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur / Hubertus Huvermann

In her text on Untitled, Sophia Trollmann notes that in 1964, when commenting on approaches to volume, Judd stated “Three dimensions are real space. […] Actual space is intrinsically more powerful and specific than paint on a flat surface” (Kerber 1977, in Trollmann n.d.).

Judd in general sought an unmediated experience of his works, supporting a new American art which rejected the significance of representational space over real space, and – his works being intended as a physical experience on a human scale – “their potential interpretation does not extend beyond the object itself; they are not symbols for something else.”. The viewer creates the relationship with the artwork, and in this case, with the topography itself (Trollmann n.d.).

In Untitled, we see the fundamental element represented by the sculpture is the topography. Through the sculpture the place becomes a space, and with viewer interaction it again becomes a place.

Considering Dan Graham’s Octagon for Munster (Fig. 3), Ronja Primke calls it “an allusion to the tradition of the so-called pleasure pavilion that since the baroque had become a standard feature of any laid-out park or palace grounds as a venue for social gatherings and festivities” (Primke n.d.). König also reflects on the theoretical implications of the pavilion as a place of public art, extending his considerations to “the park as the oldest democratic form which we have of public architecture” (König 2005: 10).

Fig. 3 Dan Graham, 1987, Oktogon für Münster [Octagon for Münster], Temporary installation in the avenue of the southern part of Schlossgarten, Münster, and various locations thereafter during 1988, 1997/98, 2007 and 2017. [Height 240 cm, diameter 365 cm, Octagonal pavilion with two-way mirrored glass, metal and wood] (Collection of LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur, Münster) Photo from 2017 installation: LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur / Hanna Neandar

On Michael Asher’s Trailer in Various Locations (Fig. 4), König considers it “a metaphor for mobility, and for understanding the relationships, social relationships, within a city.” (König 2005: 10).

Fig. 4 Michael Asher, 1977, Trailer in Changing Locations, Temporary installation in various locations over 19 weeks, Münster, and on three occasions thereafter during 1987, 1997 and 2007. [rented white caravan; weekly printed handout with descriptive text, maps, nineteen locations; documentary photographs of the caravan’s placement; and viewer search or happenstance] ((Collection of LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur, Münster) Photo from 2007 installation: LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur / Roman Mensing

The sculpture was not the caravan itself, but the multi-dimensional and multi-faceted dynamic experience of the participants. A dynamic, temporary sculpture spread over a city.

Over a period of four decades the work evolved – much as the long term spatial transformation project of Schlieren (Wandeler 2019; Fig. 1) – always with the same model of rented caravan and the same locations, although the city backdrop was changing and during some weeks of the later installations the caravan had to be stored temporarily as the sites were no longer accessible.

Asher’s work was progressive in many ways, including the concept of displacing the labour for installation and photographic documentation of the project and its successive editions onto the institution that owned the work.

Expanded Ecologies: Perspectives in a Time of Emergency

My thoughts on spatial representation have evolved after reading König’s essay, and after following other avenues of research on the Münster Skulptur Projekte. I wondered how I could explore the concepts of place and space within a recurring theme of my work which is ecocritical analysis.

I revisited the essays, in-situ works, and ephemeral actions of the exhibition ‘Expanded Ecologies: Perspectives in a Time of Emergency’ (Vitali 2009). The exhibition hadn’t been on my radar at that time, but being underpinned by ecocritical considerations I’d acquired the catalogue in 2017 for future reference.

As Anna Kafetsi, Director of the Greek National Museum of Contemporary Art points out in her foreword, it is in new inter-human and subjective relationships of the individual with private and public space, groups and communities, the body and time, that philosopher-psychoanalyst Félix Guattari sought the content of his three ecologies: the environmental, the social, and the mental. Kafetsi reflects that “public space and the environment, in broad terms – in which diverse potential definitions and realities meet and intersect, such as the local, natural, urban and social environment, the global community and cyberspace, nature and culture – inspire, mobilise, provide creative opportunities …” (Kafetsi 2009).

Daphne Vitali, curator of the exhibition, notes that what is needed is a “new approach, one that considers man as part of the ecosystem, rather than treating man and nature as two concepts (Vitali 2009: 25).

For simplicity, I term this eco-egalitarianism, alternatively in the context of Guattari’s philosophy it can be considered as a perspective which embodies the concept of otherness.

“Ecological Thinking is not simply thinking about ‘the environment’ […]. It is a revised mode of engagement with knowledge, subjectivity, politics, ethics, science, citizenship, and agency that pervades and reconfigures theory and practice”

(Code 2006, in Vitali 2009:25)

Guattari’s ecosophy moves beyond the binary consideration of nature and humankind into a multifoiled consideration of physical and mental interconnectedness, where one embodies the other. To exploit nature or others, becomes self-exploitation.

It’s in this context that I identify with the artists in this exhibition who “have not created works ‘for’ the environment but, rather, works which encourage us to think over the social, political and cultural condition”. The installations do not preach, nor berate the destruction of the environment, rather they ask us “to think about the relationship of the urban and natural environment; the individual, nature and society; nature and technology; architecture and ecology” (Vitali 2009: 28).

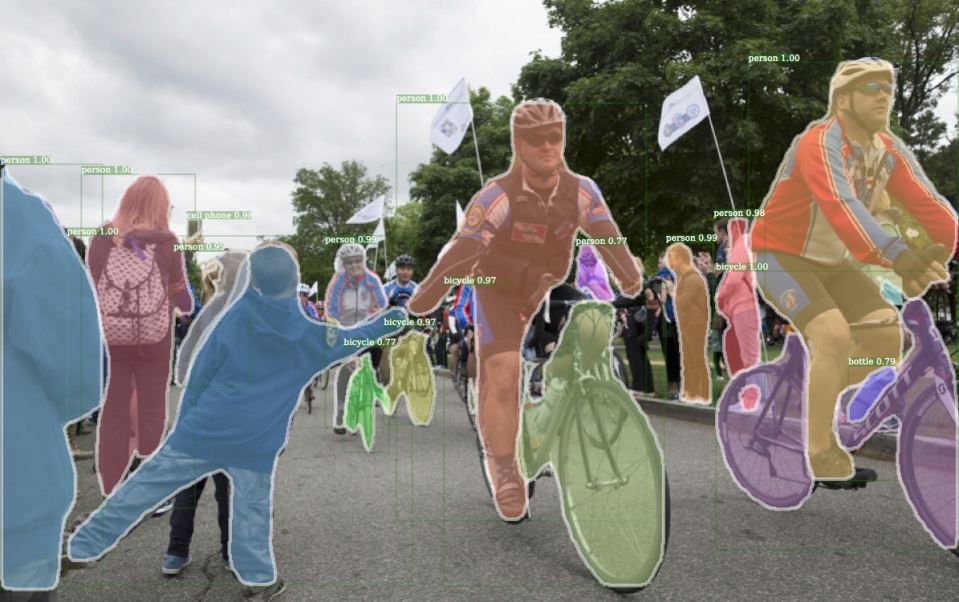

Modern Illusion (Fig. 5), a sculptural installation by Giorgos Gyparakis, comments on the illusionistic experience of nature in cities. Nature is introduced in the urban landscape in an attempt to heal the city, but this is treating the ailment, not dealing with its underlying cause.

Fig. 5 Giorgos Gyparakis, 2009, Modern Illusion, Temporary installation in the grounds of the Athens Conservatory from June 12th until October 4th, 2009. [Sculptural installation] Photo from installation / EMST (2009)

I first came across Gyparakis’ work (Fig. 5) in 2017 as a digital representation accompanied by text. I was unaware if there was actually ever an installation, or only the digital concept for one. Now experiencing the installation through photographic representation in 2020, for me the original artwork remains the digital one. I find this an interesting thought within the context of expanded ecologies, which also include the reality of cyberspace and digital representation.

Modern Illusion was first and foremost an idea, a concept, then a code, then a digital spatial representation on screen and print, then an installation, then a photograph. A sculpture in multiple dimensions.

On the fundamental, or elementary characteristic of the place where it is installed, in Modern Illusion we see cohabitation of buildings and nature in the dense urban environment of Athens, but it is an uncomfortable symbiosis. Not an egalitarian one.

A Submissive Acknowledgement of Powerlessness

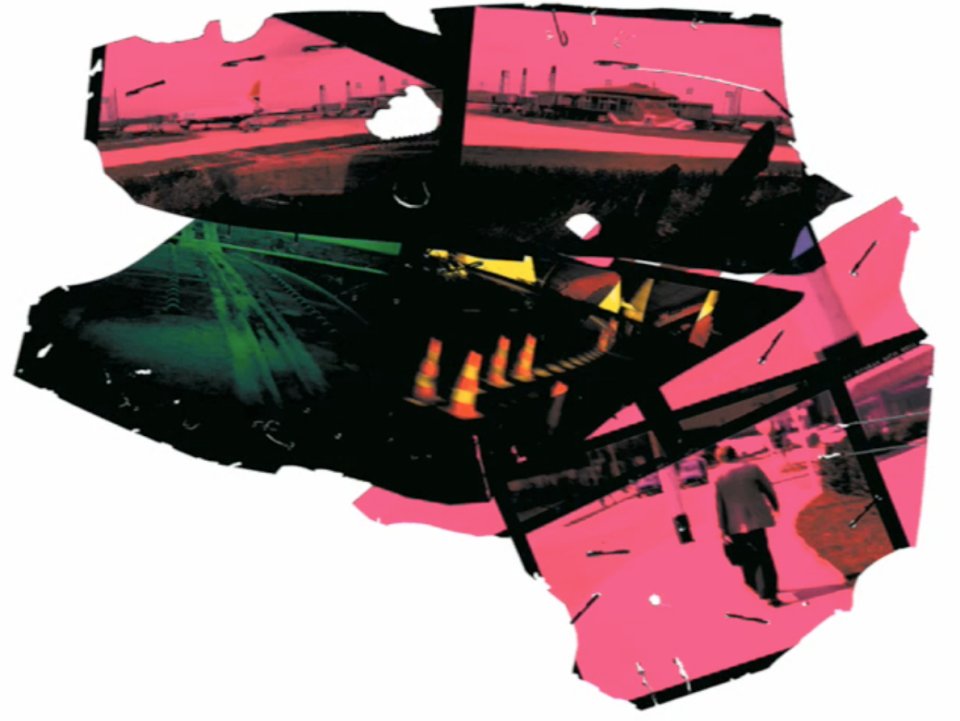

Revisting Expanded Ecologies: Perspectives in a Time of Emergency led me to explore recent work of Andreas Angelidakis, who works at the intersection of art and architecture.

In his exhibition ‘A Submissive Acknowledgement of Powerlessness’ which took place in Athens in the summer of 2019, Angelidakis continued to explore architecture as surfaces and volumes which emerge from the external forces that shape our built environment. Reflecting on the graffiti splattered buildings of downtown Athens, Angelidakis appears to be asking if nowadays the only way for a building to have something meaningful to say is to have a layer of text on it (The Breeder 2019).

“As graffiti covers weak modernist buildings shaped by petty profit margins and corrupt governance, they become reactionary, political, buildings with a voice”

(The Breeder 2019)

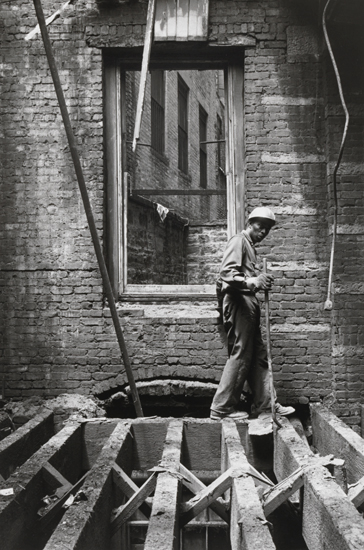

In the seating piece from the series ‘Domestic Ruins’, the forms are recognizable as deconstructed elements of modernist and post-modernist buildings (Fig. 6). Clear vinyl reveals the sofa padding and the surface is given a voice with the repeated statement “Ignoring Conceptual Contradictions”.

Fig. 6 Andreas Angelidakis, 2019, Seating piece from the series of ‘Domestic Ruins’, Gallery installation at The Breeder, Athens, from 30 May until August 31, 2019 [Installation, Clear vinyl and foam padding]

Ultimately, the question also arises, if by sitting on them in a gallery we also declare our complicity?

The heart of the matter

In responding to my question “if space doesn’t necessarily have a dimension, what is actually being represented in a photograph?” I’ve been guided by my consideration of three-dimensional space through the recognizable and tangible volumes of sculpture.

To the three-dimensions of sculpture, I would immediately add a fourth dimension, which is that of time. In particular temporary or moving installations allow the viewer to experience the concept of time. Each viewer also adds another dimension to the works, so they become multi-dimensional.

In each of the sculptures that I explored, the artists have identified a fundamental, or fundamentals, of the place and created a sculptural space in which the viewer can experience those fundamentals.

As such it seems that the artwork is a conceptual space which, with the viewer’s sentient interaction, becomes a new place.

In my use of photography and the recurrent motifs of cityscapes, buildings and infrastructure, it appears that I use spatial representation to create spaces within which the viewer creates and inhabits a new place.

Further, looking at my work through the lens of Guattari’s three ecologies, I realise that my Final Major Project is neither a series of photographs, nor a book, it is the creation of new places through viewer interaction with the images and myself, the photographer.

These new places are constructed from the fundamentals of my project’s theme, as embedded in the photographs.

Sources

EMST (2009) Installation shots from the exhibition Expanded Ecologies: Perspectives in a Time of Emergency. Available at http://fixit-emst.blogspot.com/2009/08/expanded-ecologies.html [Accessed 3 March 2020]

Kafetsi, A (2009) Foreword. In: D. Vitali (ed.) Expanded Ecologies: Perspectives in a Time of Emergency. Athens: National Museum of Contemporary Art. ISBN 978-9-60834-939-0

König, K. (2005) Not to occupy a place, but to create space. Proceedings of the synonymous Conference (22 February 2005). Fundación ICO. ISBN 978-84-934684-3-9

Primke, R. (n.d.) Oktogon für Münster [Octagon for Münster]. Available at https://www.skulptur-projekte-archiv.de/en-us/1987/projects/50/ [Accessed 3 March 2020]

Trollmann, S. (n.d.) Donald Judd, Untitled, 1976/77, 51°56’59.3″N 7°36’04.8″E. Available at https://www.kunsthallemuenster.de/en/collection/donald-judd-ohne-titel-197677-5156593n-736048e/ [Accessed 3 March 2020]

Skulptur Projekte Archive (n.d.) Michael Asher: Trailer in Various Locations. Available at https://www.skulptur-projekte-archiv.de/en-us/2007/projects/91/ [Accessed 3 March 2020]

Sutherland, G. (2019) On the search for new dimensions. Critical Research Journal blog post. Available at https://gordonsutherland.home.blog/2019/09/29/29-09-19-on-the-search-for-new-dimensions/ [Accessed 7 March 2020]

Tate (n.d.) Art Term: Sculpture. Available at https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/s/sculpture [Accessed 7 March 2020]

The Breeder (2019) Andreas Angelidakis: A Submissive Acknowledgement of Powerlessness (May 30, 2019 – August 31, 2019. Available at http://thebreedersystem.com/activity/andreas-angelidakis-a-submissive-acknowledgment-of-powerlessness-at-the-breeder/ [Accessed 3 March 2020]

Wandeler, M. (2019) Schlieren: Spatial Transformation in a Suburban Municipality in Switzerland. In: F. Giertsberg (ed.) Framed Landscapes: European Photography Commissions 1984-2019. Exhibition Catalogue, Museo ICO, 6 June to 8 September 2019. Madrid: Fundación ICO. ISBN 978-84-936568-9-8

Vitali, D. (2009) Expanded Ecologies. In: D. Vitali (ed.) Expanded Ecologies: Perspectives in a Time of Emergency. Athens: National Museum of Contemporary Art. ISBN 978-9-60834-939-0